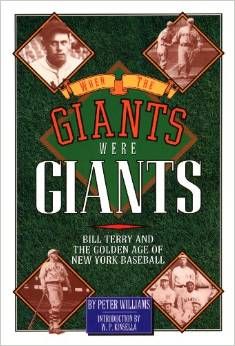

When the Giants Were Giants: Bill Terry and the Golden Age of New York Baseball by Peter Williams (Author), W. P. Kinsella (Introduction)

All that, however, was still a few hours away. Right now McGraw was following up a tip. He had probably already talked to Tom Watkins, the owner of the Chicks, after the teams played in Jackson, since Watkins made it his business to scrutinize everybody who played ball in the Memphis area. He had certainly talked to Kid Elberfeld, who managed the Little Rock, Arkansas, team in the Texas League.

McGraw and Elberfeld went back a long way. They had played against each other for a couple of years in the National League at the end of the century. In 1901, when they both jumped to the American League, they played against each other for a year and a half more, until midway through the 1902 season, when McGraw was hired to manage the Giants. McGraw always trusted the judgment of old-timers, and he certainly trusted Elberfeld's. Sometime after the Giants had broken camp in San Antonio, but before their train pulled into Memphis from Jackson late that Friday night, Elberfeld had contacted McGraw and told him an odd story.

There was, it seemed, a left-handed pitcher who'd had two good years with the Shreveport Gassers, also in the Texas League—a solid enough prospect for Elberfeld to buy out his contract when lie took over as manager of Little Rock in 1918. The pitcher, however, told Elberfeld that he had a family to support, and he said that baseball, especially minor-league baseball, was getting too chancy as a career, what with the impending American involvement in the Great War. Looking back, Elberfeld had to admit the pitcher had been right, since in 1918 the minor leagues were in such a shambles that only- one league finished the season. McGraw probably began to wonder why Elberfeld was going on like this about some pitcher who'd quit the game four years ago. But Elberfeld kept talking. Elberfeld said that after this pitcher left baseball, he had started working for Standard Oil of Louisiana, which had an office in Memphis, and that for the past year or so he'd been the star of its company team. The team had played some games in August in Arkansas, where Elberfeld had seen the kid pitch. If anything, he looked even better than when he was with Shreveport—and he could hit. Elberfeld admitted he had tried one more time to convince him to play for Little Rock, offering him more money, but the pitcher had refused, saying that the long-range situation in the minors was still far from stable and that Standard Oil was treating him well. The pitcher said he would consider an offer from a big-league team, though, there being hardly any danger of a big-league squad folding. That, Elberfeld said, was why he was suggesting him to McGraw.

Had this recommendation not come from an old baseball man like Elberfeld, McGraw might have dismissed it, since it was unusual to hear such praise for a man who hadn't played a real league game in four years. The tip had come from Elberfeld, though, so McGraw asked the Giants' secretary to arrange a meeting. He was going to offer the young left-hander a job—at a low salary, of course, but it was still a job with the Giants. Now the phone in McGraw's Peabody suite rang; the man from the desk announced that someone was there to see him, and McGraw said to send him on up. It's sad that nobody ever seems to be around to record the apparently trivial first encounters that turn out to be Great Moments.

The young man who walked into McGraw's suite in the Peabody that Saturday morning—let the record show that it was April 1, 1922— was much bigger than McGraw. He was tall and muscular, well dressed, and entirely self-assured. Although his demeanor was mature and confident, he was only twenty-three. When they shook, McGraw noticed that his hands were unusually large, even for a six-footer. His grip was firm but not threatening, and he looked at John McGraw without glancing away. McGraw must have asked him to sit down, and he took off his hat—he always wore a hat—and did. There are several versions of what happened next, most originating from the young man himself, who was, of course, Bill Terry.

Terry would go on to record the thirteenth highest career batting average in baseball history, to gain a reputation as a deceptively fast runner and possibly the greatest of all first basemen in the field, to distinguish himself as the last National Leaguer to bat over .400 in a season, and to become a remarkable manager. But he was always, above all else in life, a family man. He already had one child, four-year-old Bill, Jr., and was devoted to his wife, who had been his childhood sweetheart not that twenty-three is so far from childhood. He had even left the Baptist faith and joined the Episcopal Church because she was Episcopalian. He was a man of family and of sincere convictions, and those were his priorities at that moment, as they would be throughout his life. Sitting in the hotel suite with the great John McGraw, Terry was asked if he wanted to play for the best team in the history of modern baseball, a team that, in 1922, was at its absolute peak and had five future Hall-of-Famers among the first six players in the batting order: George Kelly, Frank Frisch, Dave Bancroft, Ross Youngs, and Casey Stengel. (The only one of the six players who wouldn't make it to the Hall was Heinie Groh, who had hit .331 the year before and was presently batting cleanup.) Terry calmly asked McGraw how much he would be paid. McGraw was startled. He answered by asking Terry how much he wanted. Terry named a figure that was at least equal to his Standard Oil paycheck, maybe a little higher. McGraw said it was too much. Terry politely declined the offer and got tip to leave.

Some say McGraw was thunderstruck, and he probably was. Here was a courteous, dignified, soft-spoken, clean-cut young man, a man who carried himself like the Giants' legendary Christy Mathewson, being offered a chance to realize every boy's dream, and he was asking about a salary. McGraw explained the portentousness of the situation: Don't you realize what I'm offering? A chance to play baseball in the Polo Grounds, with the— New York Giants? Terry did, of course, but he also knew what was most important to him. If he accepted the job at a cut in pay, he would make life a little harder for his wife and son. For Terry that made it a simple choice—no choice at all.

Since the several versions of this story all originate with Terry himself, they differ only in detail. Here is his last account of what happened after he asked McGraw what his salary with the Giants would be: "And he asked me how much money I wanted. I said, 'I want a three-year contract. Eight hundred dollars a month to start.' `Oh, I'm sorry, I can't do that,' he said. And I said, `Well, no use us talking anymore,' and I said, 'Nice to see you,' and I took my hat."

In later years, Terry would gain a reputation as a tough bargainer it started here—but he was never a haggler. Assuming the matter was closed, he took the elevator down to the lobby and started back to his home on Vance, a quiet, shady street about two miles away. As Kid Elberfeld recognized, Terry had been very astute to quit organized ball when he did, just before the 1918 season. While the 1917 season had been relatively unaffected in the majors, the story had been different in the minors, where only twelve leagues had finished the year. Terry had finished out the 1917 season with the Shreveport Gassers, but he read the papers, and through the fall and into the winter of that year, they were full of warnings. They reported that the minors might redistrict, with some teams disappearing in the process; that players would have to sign contracts with a clause that protected the owners (but not the players) should the war force a suspension of games; and that fewer games would be played in 1918.

Ed Barrow, who would later become the Yankee general manager, was president of the International League then and he actually wanted to cancel his 1918 season; if he'd had his way, not even one minor league would have finished the year. Then the papers announced that only ten minor leagues would stall the 1918 season (half the number of the year before), and finally they reported that salaries were going to be cut. Baseball in the minors had become a severely depressed industry, not a place for any conscientious head of a household, and Bill Terry certainly knew it. If Elberfeld had bought Terry's contract from Shreveport, no offense, but that was Elberfeld's hard luck. So in early 1918, Terry started looking for profitable work. He got a stop-gap job assembling batteries, but this was essentially menial labor, so lie kept looking and finally landed a job as a salesman with Standard Oil of Louisiana.

Once on board, Terry volunteered to build the company team. His boss, Charles Scholder, told him to go ahead, and Terry quickly became the star and unofficial captain, developing a local following and becoming a popular figure in Memphis. The Standard Oil Polarises, named after a high-grade motor oil, played on Sundays and sometimes Saturdays, occasionally traveling as far as Knoxville to play in Tennessee tournaments. Terry would remain content to subordinate baseball to business for the next four years. He worked full-time for Standard through the spring of 1922, and it was a happy time for him. He was a young and ambitious man, affiliated with a major corporation that promised him a stable future; he was still playing a game that, despite what his detractors later said, he loved very much; and lie was living in Memphis with a young wife and a baby son whom he loved even more. Terry had achieved his first great goal: he had created a stable home and family—something he had never known.

To understand how important this was to him, it's best to take a look at the Terry family tree.

Product Details

'''When the Giants Were Giants: Bill Terry and the Golden Age of New York Baseball by Peter Williams (Author), W. P. Kinsella (Introduction)''' This is the story of a forgotten Giant--the man Baseball Magazine called in 1930 "baseball's greatest first baseman"--Bill Terry. Brought up from proverty and the obscurity of semipro ball in the South by the famed "Little Napoleon," manager John McGraw of the Giants, Terry developed into the team's key player in the 1920s. As America battled the Depression, the no-nonsense Terry replaced McGraw as manager of the Giants and led the team to three pennants and a world championship. In When the Giants Were Giants, author Peter Williams looks at the end of an era--a time before television, night baseball, player strikes, or free agents--through the lense of this Hall-of-Famer's career as a player and coach. Exclusive interviews with Bill Terry and other players bring to life the rich and color tapestry of Golden Age baseball when the big New York baseball teams were the biggest names in sports. (from the jacket)

Hardcover: 352 pages

Publisher: Algonquin Books; 1st edition (April 1, 1994)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0945575025

ISBN-13: 978-0945575023

Product Dimensions: 1.5 x 6.2 x 9.5 inches

Shipping Weight: 1.6 pounds

Average Customer Review: 4.0 out of 5 stars

Amazon Best Sellers Rank: #1,213,335 in Books

McGraw and Elberfeld went back a long way. They had played against each other for a couple of years in the National League at the end of the century. In 1901, when they both jumped to the American League, they played against each other for a year and a half more, until midway through the 1902 season, when McGraw was hired to manage the Giants. McGraw always trusted the judgment of old-timers, and he certainly trusted Elberfeld's. Sometime after the Giants had broken camp in San Antonio, but before their train pulled into Memphis from Jackson late that Friday night, Elberfeld had contacted McGraw and told him an odd story.

There was, it seemed, a left-handed pitcher who'd had two good years with the Shreveport Gassers, also in the Texas League—a solid enough prospect for Elberfeld to buy out his contract when lie took over as manager of Little Rock in 1918. The pitcher, however, told Elberfeld that he had a family to support, and he said that baseball, especially minor-league baseball, was getting too chancy as a career, what with the impending American involvement in the Great War. Looking back, Elberfeld had to admit the pitcher had been right, since in 1918 the minor leagues were in such a shambles that only- one league finished the season. McGraw probably began to wonder why Elberfeld was going on like this about some pitcher who'd quit the game four years ago. But Elberfeld kept talking. Elberfeld said that after this pitcher left baseball, he had started working for Standard Oil of Louisiana, which had an office in Memphis, and that for the past year or so he'd been the star of its company team. The team had played some games in August in Arkansas, where Elberfeld had seen the kid pitch. If anything, he looked even better than when he was with Shreveport—and he could hit. Elberfeld admitted he had tried one more time to convince him to play for Little Rock, offering him more money, but the pitcher had refused, saying that the long-range situation in the minors was still far from stable and that Standard Oil was treating him well. The pitcher said he would consider an offer from a big-league team, though, there being hardly any danger of a big-league squad folding. That, Elberfeld said, was why he was suggesting him to McGraw.

Had this recommendation not come from an old baseball man like Elberfeld, McGraw might have dismissed it, since it was unusual to hear such praise for a man who hadn't played a real league game in four years. The tip had come from Elberfeld, though, so McGraw asked the Giants' secretary to arrange a meeting. He was going to offer the young left-hander a job—at a low salary, of course, but it was still a job with the Giants. Now the phone in McGraw's Peabody suite rang; the man from the desk announced that someone was there to see him, and McGraw said to send him on up. It's sad that nobody ever seems to be around to record the apparently trivial first encounters that turn out to be Great Moments.

The young man who walked into McGraw's suite in the Peabody that Saturday morning—let the record show that it was April 1, 1922— was much bigger than McGraw. He was tall and muscular, well dressed, and entirely self-assured. Although his demeanor was mature and confident, he was only twenty-three. When they shook, McGraw noticed that his hands were unusually large, even for a six-footer. His grip was firm but not threatening, and he looked at John McGraw without glancing away. McGraw must have asked him to sit down, and he took off his hat—he always wore a hat—and did. There are several versions of what happened next, most originating from the young man himself, who was, of course, Bill Terry.

Terry would go on to record the thirteenth highest career batting average in baseball history, to gain a reputation as a deceptively fast runner and possibly the greatest of all first basemen in the field, to distinguish himself as the last National Leaguer to bat over .400 in a season, and to become a remarkable manager. But he was always, above all else in life, a family man. He already had one child, four-year-old Bill, Jr., and was devoted to his wife, who had been his childhood sweetheart not that twenty-three is so far from childhood. He had even left the Baptist faith and joined the Episcopal Church because she was Episcopalian. He was a man of family and of sincere convictions, and those were his priorities at that moment, as they would be throughout his life. Sitting in the hotel suite with the great John McGraw, Terry was asked if he wanted to play for the best team in the history of modern baseball, a team that, in 1922, was at its absolute peak and had five future Hall-of-Famers among the first six players in the batting order: George Kelly, Frank Frisch, Dave Bancroft, Ross Youngs, and Casey Stengel. (The only one of the six players who wouldn't make it to the Hall was Heinie Groh, who had hit .331 the year before and was presently batting cleanup.) Terry calmly asked McGraw how much he would be paid. McGraw was startled. He answered by asking Terry how much he wanted. Terry named a figure that was at least equal to his Standard Oil paycheck, maybe a little higher. McGraw said it was too much. Terry politely declined the offer and got tip to leave.

Some say McGraw was thunderstruck, and he probably was. Here was a courteous, dignified, soft-spoken, clean-cut young man, a man who carried himself like the Giants' legendary Christy Mathewson, being offered a chance to realize every boy's dream, and he was asking about a salary. McGraw explained the portentousness of the situation: Don't you realize what I'm offering? A chance to play baseball in the Polo Grounds, with the— New York Giants? Terry did, of course, but he also knew what was most important to him. If he accepted the job at a cut in pay, he would make life a little harder for his wife and son. For Terry that made it a simple choice—no choice at all.

Since the several versions of this story all originate with Terry himself, they differ only in detail. Here is his last account of what happened after he asked McGraw what his salary with the Giants would be: "And he asked me how much money I wanted. I said, 'I want a three-year contract. Eight hundred dollars a month to start.' `Oh, I'm sorry, I can't do that,' he said. And I said, `Well, no use us talking anymore,' and I said, 'Nice to see you,' and I took my hat."

In later years, Terry would gain a reputation as a tough bargainer it started here—but he was never a haggler. Assuming the matter was closed, he took the elevator down to the lobby and started back to his home on Vance, a quiet, shady street about two miles away. As Kid Elberfeld recognized, Terry had been very astute to quit organized ball when he did, just before the 1918 season. While the 1917 season had been relatively unaffected in the majors, the story had been different in the minors, where only twelve leagues had finished the year. Terry had finished out the 1917 season with the Shreveport Gassers, but he read the papers, and through the fall and into the winter of that year, they were full of warnings. They reported that the minors might redistrict, with some teams disappearing in the process; that players would have to sign contracts with a clause that protected the owners (but not the players) should the war force a suspension of games; and that fewer games would be played in 1918.

Ed Barrow, who would later become the Yankee general manager, was president of the International League then and he actually wanted to cancel his 1918 season; if he'd had his way, not even one minor league would have finished the year. Then the papers announced that only ten minor leagues would stall the 1918 season (half the number of the year before), and finally they reported that salaries were going to be cut. Baseball in the minors had become a severely depressed industry, not a place for any conscientious head of a household, and Bill Terry certainly knew it. If Elberfeld had bought Terry's contract from Shreveport, no offense, but that was Elberfeld's hard luck. So in early 1918, Terry started looking for profitable work. He got a stop-gap job assembling batteries, but this was essentially menial labor, so lie kept looking and finally landed a job as a salesman with Standard Oil of Louisiana.

Once on board, Terry volunteered to build the company team. His boss, Charles Scholder, told him to go ahead, and Terry quickly became the star and unofficial captain, developing a local following and becoming a popular figure in Memphis. The Standard Oil Polarises, named after a high-grade motor oil, played on Sundays and sometimes Saturdays, occasionally traveling as far as Knoxville to play in Tennessee tournaments. Terry would remain content to subordinate baseball to business for the next four years. He worked full-time for Standard through the spring of 1922, and it was a happy time for him. He was a young and ambitious man, affiliated with a major corporation that promised him a stable future; he was still playing a game that, despite what his detractors later said, he loved very much; and lie was living in Memphis with a young wife and a baby son whom he loved even more. Terry had achieved his first great goal: he had created a stable home and family—something he had never known.

To understand how important this was to him, it's best to take a look at the Terry family tree.

Product Details

'''When the Giants Were Giants: Bill Terry and the Golden Age of New York Baseball by Peter Williams (Author), W. P. Kinsella (Introduction)''' This is the story of a forgotten Giant--the man Baseball Magazine called in 1930 "baseball's greatest first baseman"--Bill Terry. Brought up from proverty and the obscurity of semipro ball in the South by the famed "Little Napoleon," manager John McGraw of the Giants, Terry developed into the team's key player in the 1920s. As America battled the Depression, the no-nonsense Terry replaced McGraw as manager of the Giants and led the team to three pennants and a world championship. In When the Giants Were Giants, author Peter Williams looks at the end of an era--a time before television, night baseball, player strikes, or free agents--through the lense of this Hall-of-Famer's career as a player and coach. Exclusive interviews with Bill Terry and other players bring to life the rich and color tapestry of Golden Age baseball when the big New York baseball teams were the biggest names in sports. (from the jacket)

Hardcover: 352 pages

Publisher: Algonquin Books; 1st edition (April 1, 1994)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0945575025

ISBN-13: 978-0945575023

Product Dimensions: 1.5 x 6.2 x 9.5 inches

Shipping Weight: 1.6 pounds

Average Customer Review: 4.0 out of 5 stars

Amazon Best Sellers Rank: #1,213,335 in Books