February 5, 1905 - The Inter Ocean, Chicago, IL - Special Plays

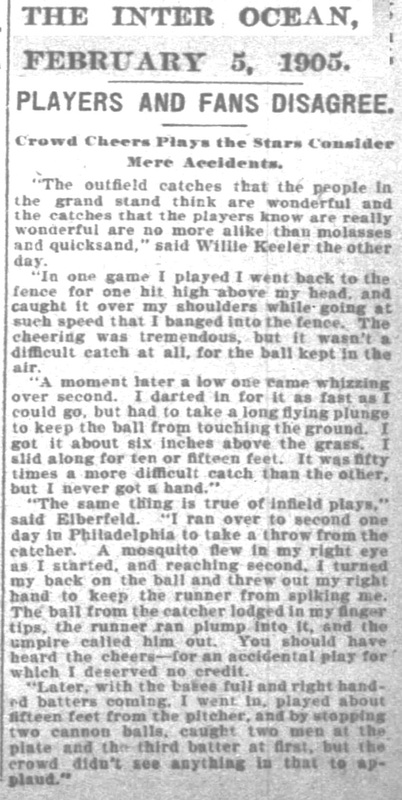

THE INTER OCEAN, FEBRUARY 5. 1905.

PLAYERS AND FANS DISAGREE.

Crowd Cheers Plays the Stars Consider Mere Accidents.

"The outfield catches that the people In the grand stand think are wonderful and the catches that the players know are really wonderful are no more alike than molasses and quicksand," said Willie Keeler the other day.

"In one game I played I went back to the fence for one hit high above my head, and caught it over my shoulders while going at such speed that I banged into the fence. The cheering was tremendous, but it wasn't a difficult catch at all, for the ball kept in the air.

"A moment later a low one came whizzing over second. I darted in for it as fast as I could go, but had to take a long flying plunge to keep the ball from touching the ground. I got it about six inches above the grass. I slid along for ten or fifteen feet. It was fifty times a more difficult catch than the other, but I never got a hand."

"The same thing is true of infield plays," said Elberfeld. "I ran over to second one day in Philadelphia to take a throw from the catcher. A mosquito flew in my right eye as I started, and reaching second. I turned my back on the ball and threw out my right hand to keep the runner from spiking low. The ball from the catcher lodged in my fingerr tips, the runner ran plumb into it, and the umpire called him out. You should have heard the cheers—for an accidental play for which I deserved no credit.

"Later, with the bases full and right handed batters coming. I went in, played about fifteen feet from the pitcher, and by stopping two cannon balls. caught two men at the plate and the third batter at first, but the

crowd didn't see anything in that to applaud."

PLAYERS AND FANS DISAGREE.

Crowd Cheers Plays the Stars Consider Mere Accidents.

"The outfield catches that the people In the grand stand think are wonderful and the catches that the players know are really wonderful are no more alike than molasses and quicksand," said Willie Keeler the other day.

"In one game I played I went back to the fence for one hit high above my head, and caught it over my shoulders while going at such speed that I banged into the fence. The cheering was tremendous, but it wasn't a difficult catch at all, for the ball kept in the air.

"A moment later a low one came whizzing over second. I darted in for it as fast as I could go, but had to take a long flying plunge to keep the ball from touching the ground. I got it about six inches above the grass. I slid along for ten or fifteen feet. It was fifty times a more difficult catch than the other, but I never got a hand."

"The same thing is true of infield plays," said Elberfeld. "I ran over to second one day in Philadelphia to take a throw from the catcher. A mosquito flew in my right eye as I started, and reaching second. I turned my back on the ball and threw out my right hand to keep the runner from spiking low. The ball from the catcher lodged in my fingerr tips, the runner ran plumb into it, and the umpire called him out. You should have heard the cheers—for an accidental play for which I deserved no credit.

"Later, with the bases full and right handed batters coming. I went in, played about fifteen feet from the pitcher, and by stopping two cannon balls. caught two men at the plate and the third batter at first, but the

crowd didn't see anything in that to applaud."