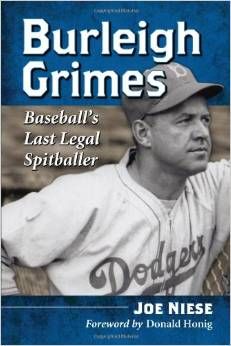

Burleigh Grimes: Baseball's Last Legal Spitballer Paperback by Joe Niese (Author), Foreword by Donald Honig (Author)

Burleigh Grimes

Chattanooga is located in southeastern Tennessee on the banks of the Tennessee River. Like many early twentieth century Southern cities, Chattanooga boasted a booming iron and steel industry. It was a world away from the Grimes family farm in Wisconsin, and the next few months changed young Burleigh's life forever. Not yet out of his teens, he was introduced to Southern culture, played against a higher caliber of ballplayers than be had ever seen, wooed and married his first wife, and was influenced by a man who changed his in-game personality forever. Named for nearby Lookout Mountain, the Chattanooga Lookouts had been a part of the eight-team Southern Association since that circuit succeeded the disbanded Southern League in 1901. The Lookouts never finished higher than fourth in that time and had finished in seventh the year before. They played their games at Andrews Field, built in 1910 by the team's owner, Chattanooga businessman Oliver Burnside (0.13.) Andrews. Located on East Third Street near the busy Southern Railway station, the field had a concrete foundation and drab, poorly constructed wooden bleachers that seated nearly 5,000. The bleachers had been so shoddily built that in January of 1914, carpenters who were doing their annual repairs "expressed surprise that they had not collapsed last season." Grimes arrived in Chattanooga on a rare off day.

First-year Lookouts manager Norman Elberfeld had called off practice to give his depleted pitching stall some rest. Nicknamed "The Tabasco Kid" or "Kid" for his feisty demeanor, Elberfeld, who was playing shortstop in addition to his managerial duties, was beloved by his players and despised by seemingly everyone else. He was once described as "the dirtiest, scrappiest, most pestiferous, most rantankerous (sp), most rambunctious ball player that ever stood on spikes." In 1905 Elberfeld had given a Detroit Tigers rookie a rude welcome to the major leagues. While the youngster slid headfirst into second base, Elberfeld buried his knee into the ballplayer's neck, quickly cutting off his air supply. The rookie gasped for air as lie struggled to get Elberfeld off him. The ballplayer's name was Ty Cobb and he never made the mistake of sliding headfirst again. Elberfeld was said to have initiated Grimes into umpire baiting, bench jockeying and all-around intimidation on the diamond. Grimes's obedience to his manager earned him an immediate reputation that followed him into the professional game and made him a marked man at times.

Years later, Grimes explained Elberfeld's influence on him. was an 18-year-old [sic] country boy. I'd been driving a four- horse team in a lumber camp for $35 a month, so when Elberfeld signed me for $150 per, I thought that was all the money in the world and that he was the greatest man. Being of such sentiments, I naturally did everything he told me to.'' With the Lookouts already having an established four-man rotation, Grimes was slated to serve as a reliever and spot starter in Chattanooga. His move to the Southern Association was an obvious step up in the level of corn- petition, as a number of former and soon-to-be major leaguers graced the league's rosters. One of those players was the Lookouts' ace pitcher. Harry Coveleski, who was putting together one dominating performance after another. Nicknamed the "Giant Killer" for having defeated John McGraw's Giants three times in five days to keep them from winning the 1908 National League pennant, Coveleski had spent the past four seasons in the Southern Association trying to recapture that magic. Elberfeld tabbed Grimes to start a June 12 home game against the Atlanta Crackers. After giving up a run in the top of the first, he cruised through until the fifth with the aid of his battery mate, Gabby Street, who threw out three would-be base stealers. In the sixth inning, Grimes lost his control and surrendered five runs on three hits, two walks, and a hit batsman before being removed from the game.

Grimes's next start was against the second-place Nashville Volunteers. He proved his worth to his teammates, giving up five hits in a 12-inning complete-game victory that leapfrogged the Lookouts into second place. He also caught the eye of a female admirer who had taken in the game. That evening, he and Gabby Street were dissecting the day's game while dining at their hotel when Grimes received a phone call. On the other end of the line was a fan from Atlanta by the name of Florence Ruth Patten. The two conversed for a while before deciding to get together for a date later that evening. As the season progressed, it became apparent that a promotion to the Tigers wasn't going to happen. That didn't seem to matter, as Grimes soaked up life on and A' the diamond. He visited his first ocean — the Atlantic — and enjoyed cookouts at the Elberfeld homestead in North Chattanooga. He mingled so easily among the locals that at times he was even mistaken for one. He developed a faux Southern drawl and concocted a family history in which his Grandfather Elias had come to Wisconsin as a youngster when ""he traveled up the Mississippi River after contracting malaria while in Nashville."

Elberfeld wasn't the only one who taught Grimes lessons about intimidation. He was sometimes the recipient of the opposition's tactics. At the time it was customary for all fielders, including the pitcher, to leave their gloves on the field while their team was at bat. Grimes followed suit, even going so far as to throwing his wad of slippery elm into his mitt when he retired to the bench. He had been doing this since his (lays on the Yellow Jackets, but soon encountered trouble: "I'd put the elm in my glove and drop the works between the mound and the dugout after each inning. But those guys on other teams would kick my glove and get my elm full of dirt."

The Lookouts ended the season in fourth place at 70-64. Grimes finished with a pedestrian 6-7 record, but his defense was gaining rave reviews. In the bunt-heavy Dead Ball Era, a pitcher needed to know how to field his position, and Grimes did so impeccably. Going against the common practice of throwing with his right foot planted parallel to the rubber, Grimes "developed an unorthodox stance—he simply faced the plate squarely, planting his right foot at only a slight angle to the plate. Burleigh insisted he could throw harder and do more things about base runners than if he threw by pushing off in the conventional way." The highlight of Grimes's season took place off the field on the morning of August 9. Just nine days before his 20th birthday and some five weeks after their first date, Burleigh Grimes and Ruth Patten were married in front of teammates at Kid Elberfeld's home.

It was the first of five marriages for Grimes and marked the beginning of an at times tumultuous seventeen-year union. With only a verbal agreement that he would be back in Chattanooga in 1914, Grimes and his bride returned to his family's farm in Clear Lake. Once again, there were ballgames to he played and work to be done on the farm. Only a few months into their marriage, problems were already arising between the newlyweds. A big-city Southern girl, Ruth had trouble adjusting to life on a Wisconsin farm: she didn't like living in Clear Lake and couldn't seem to get along with Grimes's parents or his siblings.Her frustration with the situation came to a head one clay when she wanted to take a picture with Burleigh, who had been in the fields driving a grain wagon. Wearing overalls and a straw hat, he approached her on the porch. She urged him to remove the hat, but he refused and an argument ensued. Ruth ended it when she threw "the camera on the porch floor, stamped it to pieces and then kicked the pieces into the yard."

When the fall harvest was finished, Grimes headed back into the woods for another winter of driving horses for $35 a month. Upon informing his fellow lumberjacks that he was set to receive $175 a month to play ball for Chattanooga in the spring, his bunkmates were indignant. Years later, he explained their incredulous reaction: "They don't mind a good liar up there, but they want him to use a little judgment in his lies. That was too raw for them to swallow."

Product Information

'''Burleigh Grimes: Baseball's Last Legal Spitballer Paperback by Joe Niese (Author), Foreword by Donald Honig (Author)''' Burleigh Grimes--forever remembered as the ill-tempered spitballer with the perpetual five o'clock shadow. For nearly two decades, he brought his surly disposition to the pitcher's mound. His life-or-death mentality resulted in a reputation as one of the game's great competitors and a spot in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Along the way he suited up for eight different ball clubs and played alongside a record 36 Hall of Famers. In all, Grimes spent over half a century in professional baseball as a player, manager, coach and scout. This biography covers all aspects of his life. From his early childhood in Clear Lake, Wisconsin, to his twilight years in that same town. In between are World Series highs and lows, brawls, five marriages, a near-death experience and 270 major league victories.

Product Details<br> Paperback: 244 pages

Publisher: McFarland (April 22, 2013)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0786473282<br> ISBN-13: 978-0786473281

Product Dimensions: 8.9 x 6 x 0.7 inches

Shipping Weight: 12 ounces

Average Customer Review: 4.5 out of 5 stars

Amazon Best Sellers Rank: #1,501,112 in Books

Chattanooga is located in southeastern Tennessee on the banks of the Tennessee River. Like many early twentieth century Southern cities, Chattanooga boasted a booming iron and steel industry. It was a world away from the Grimes family farm in Wisconsin, and the next few months changed young Burleigh's life forever. Not yet out of his teens, he was introduced to Southern culture, played against a higher caliber of ballplayers than be had ever seen, wooed and married his first wife, and was influenced by a man who changed his in-game personality forever. Named for nearby Lookout Mountain, the Chattanooga Lookouts had been a part of the eight-team Southern Association since that circuit succeeded the disbanded Southern League in 1901. The Lookouts never finished higher than fourth in that time and had finished in seventh the year before. They played their games at Andrews Field, built in 1910 by the team's owner, Chattanooga businessman Oliver Burnside (0.13.) Andrews. Located on East Third Street near the busy Southern Railway station, the field had a concrete foundation and drab, poorly constructed wooden bleachers that seated nearly 5,000. The bleachers had been so shoddily built that in January of 1914, carpenters who were doing their annual repairs "expressed surprise that they had not collapsed last season." Grimes arrived in Chattanooga on a rare off day.

First-year Lookouts manager Norman Elberfeld had called off practice to give his depleted pitching stall some rest. Nicknamed "The Tabasco Kid" or "Kid" for his feisty demeanor, Elberfeld, who was playing shortstop in addition to his managerial duties, was beloved by his players and despised by seemingly everyone else. He was once described as "the dirtiest, scrappiest, most pestiferous, most rantankerous (sp), most rambunctious ball player that ever stood on spikes." In 1905 Elberfeld had given a Detroit Tigers rookie a rude welcome to the major leagues. While the youngster slid headfirst into second base, Elberfeld buried his knee into the ballplayer's neck, quickly cutting off his air supply. The rookie gasped for air as lie struggled to get Elberfeld off him. The ballplayer's name was Ty Cobb and he never made the mistake of sliding headfirst again. Elberfeld was said to have initiated Grimes into umpire baiting, bench jockeying and all-around intimidation on the diamond. Grimes's obedience to his manager earned him an immediate reputation that followed him into the professional game and made him a marked man at times.

Years later, Grimes explained Elberfeld's influence on him. was an 18-year-old [sic] country boy. I'd been driving a four- horse team in a lumber camp for $35 a month, so when Elberfeld signed me for $150 per, I thought that was all the money in the world and that he was the greatest man. Being of such sentiments, I naturally did everything he told me to.'' With the Lookouts already having an established four-man rotation, Grimes was slated to serve as a reliever and spot starter in Chattanooga. His move to the Southern Association was an obvious step up in the level of corn- petition, as a number of former and soon-to-be major leaguers graced the league's rosters. One of those players was the Lookouts' ace pitcher. Harry Coveleski, who was putting together one dominating performance after another. Nicknamed the "Giant Killer" for having defeated John McGraw's Giants three times in five days to keep them from winning the 1908 National League pennant, Coveleski had spent the past four seasons in the Southern Association trying to recapture that magic. Elberfeld tabbed Grimes to start a June 12 home game against the Atlanta Crackers. After giving up a run in the top of the first, he cruised through until the fifth with the aid of his battery mate, Gabby Street, who threw out three would-be base stealers. In the sixth inning, Grimes lost his control and surrendered five runs on three hits, two walks, and a hit batsman before being removed from the game.

Grimes's next start was against the second-place Nashville Volunteers. He proved his worth to his teammates, giving up five hits in a 12-inning complete-game victory that leapfrogged the Lookouts into second place. He also caught the eye of a female admirer who had taken in the game. That evening, he and Gabby Street were dissecting the day's game while dining at their hotel when Grimes received a phone call. On the other end of the line was a fan from Atlanta by the name of Florence Ruth Patten. The two conversed for a while before deciding to get together for a date later that evening. As the season progressed, it became apparent that a promotion to the Tigers wasn't going to happen. That didn't seem to matter, as Grimes soaked up life on and A' the diamond. He visited his first ocean — the Atlantic — and enjoyed cookouts at the Elberfeld homestead in North Chattanooga. He mingled so easily among the locals that at times he was even mistaken for one. He developed a faux Southern drawl and concocted a family history in which his Grandfather Elias had come to Wisconsin as a youngster when ""he traveled up the Mississippi River after contracting malaria while in Nashville."

Elberfeld wasn't the only one who taught Grimes lessons about intimidation. He was sometimes the recipient of the opposition's tactics. At the time it was customary for all fielders, including the pitcher, to leave their gloves on the field while their team was at bat. Grimes followed suit, even going so far as to throwing his wad of slippery elm into his mitt when he retired to the bench. He had been doing this since his (lays on the Yellow Jackets, but soon encountered trouble: "I'd put the elm in my glove and drop the works between the mound and the dugout after each inning. But those guys on other teams would kick my glove and get my elm full of dirt."

The Lookouts ended the season in fourth place at 70-64. Grimes finished with a pedestrian 6-7 record, but his defense was gaining rave reviews. In the bunt-heavy Dead Ball Era, a pitcher needed to know how to field his position, and Grimes did so impeccably. Going against the common practice of throwing with his right foot planted parallel to the rubber, Grimes "developed an unorthodox stance—he simply faced the plate squarely, planting his right foot at only a slight angle to the plate. Burleigh insisted he could throw harder and do more things about base runners than if he threw by pushing off in the conventional way." The highlight of Grimes's season took place off the field on the morning of August 9. Just nine days before his 20th birthday and some five weeks after their first date, Burleigh Grimes and Ruth Patten were married in front of teammates at Kid Elberfeld's home.

It was the first of five marriages for Grimes and marked the beginning of an at times tumultuous seventeen-year union. With only a verbal agreement that he would be back in Chattanooga in 1914, Grimes and his bride returned to his family's farm in Clear Lake. Once again, there were ballgames to he played and work to be done on the farm. Only a few months into their marriage, problems were already arising between the newlyweds. A big-city Southern girl, Ruth had trouble adjusting to life on a Wisconsin farm: she didn't like living in Clear Lake and couldn't seem to get along with Grimes's parents or his siblings.Her frustration with the situation came to a head one clay when she wanted to take a picture with Burleigh, who had been in the fields driving a grain wagon. Wearing overalls and a straw hat, he approached her on the porch. She urged him to remove the hat, but he refused and an argument ensued. Ruth ended it when she threw "the camera on the porch floor, stamped it to pieces and then kicked the pieces into the yard."

When the fall harvest was finished, Grimes headed back into the woods for another winter of driving horses for $35 a month. Upon informing his fellow lumberjacks that he was set to receive $175 a month to play ball for Chattanooga in the spring, his bunkmates were indignant. Years later, he explained their incredulous reaction: "They don't mind a good liar up there, but they want him to use a little judgment in his lies. That was too raw for them to swallow."

Product Information

'''Burleigh Grimes: Baseball's Last Legal Spitballer Paperback by Joe Niese (Author), Foreword by Donald Honig (Author)''' Burleigh Grimes--forever remembered as the ill-tempered spitballer with the perpetual five o'clock shadow. For nearly two decades, he brought his surly disposition to the pitcher's mound. His life-or-death mentality resulted in a reputation as one of the game's great competitors and a spot in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Along the way he suited up for eight different ball clubs and played alongside a record 36 Hall of Famers. In all, Grimes spent over half a century in professional baseball as a player, manager, coach and scout. This biography covers all aspects of his life. From his early childhood in Clear Lake, Wisconsin, to his twilight years in that same town. In between are World Series highs and lows, brawls, five marriages, a near-death experience and 270 major league victories.

Product Details<br> Paperback: 244 pages

Publisher: McFarland (April 22, 2013)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0786473282<br> ISBN-13: 978-0786473281

Product Dimensions: 8.9 x 6 x 0.7 inches

Shipping Weight: 12 ounces

Average Customer Review: 4.5 out of 5 stars

Amazon Best Sellers Rank: #1,501,112 in Books