Sam Leever

This article was written by Mark Armour.

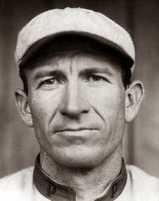

With piercing blue eyes and brown hair that was thinning even early in his baseball career, Sam Leever was known as "The Goshen Schoolmaster," as much for his appearance and serious disposition as for his off-season disposition. Leever relied on his exceptional curveball and control to compile a record of 194-100, for a .660 winning percentage, the ninth highest in baseball history. In an era when pitchers were listed in the newspapers each week according to their winning percentages, the oft-injured right-hander was the National League's "leading pitcher" in 1901, 1903, and 1905. The fourth of Edward and Amerideth Leever's eight children, Samuel Leever was born on December 23, 1871, on a farm in Goshen, Ohio, about twenty miles northeast of Cincinnati. Like many of their neighbors, the Leevers were of Pennsylvania German heritage. After graduating from Goshen High School, Leever taught there for seven years before he signed his first baseball contract at the advanced age of 25. A star pitcher for several years on club teams in southwestern Ohio, Leever was a teammate of future major leaguer Kid Elberfield with the local Norwood Maroons. He taught school during the week and pitched on Sundays. A big strong right-hander with an exceptional curveball, Leever was not signed sooner likely because he was not a hard thrower-he relied more on control and the movement of his pitches. An oft-told legend, undoubtedly apocryphal, claimed that Barney Dreyfuss, then the owner of the Louisville Colonels, discovered Leever while he was playing "Anthony Over," a game that required tossing a ball over a barn to a friend. Leever was apparently able to curve the ball around the barn instead. His first professional season was 1897 with Richmond of the Atlantic League, where he won 20 games and led the league in strikeouts. Pittsburgh purchased his contract for 1898, but when he reported with a sore arm the club sent him back to Richmond, where he won 14 more games and helped lead his team to the league championship. His success earned him a recall to Pittsburgh for the tail end of the season, and he won his only decision. As an 1899 rookie, Leever pitched in a league-leading 51 games and 379 innings, and compiled a record of 21-23. Manager Patsy Donovan not only let him complete 35 games, Leever also led the league by finishing 11 games for other pitchers and by saving (as retroactively calculated) three games. Though a sore right arm nagged him occasionally throughout his career, Leever never had another losing season, and never again had an ERA as high as 3.00. During the years 1900-1902, with an exceptionally deep and talented pitching staff at his disposal, manager Fred Clarke used what amounted to a five-man rotation most of the time, thus preventing any of his great pitchers from accumulating huge win totals. Leever won 44 and lost 25 over these three years, leading the league in winning percentage (.737) in 1901. Following the 1902 seasons, fellow pitching stalwarts Jack Chesbro and Jesse Tannehill jumped to the New York Highlanders of the American League, and Leever and his good friend Deacon Phillippe were accordingly called on to carry a much larger burden in 1903. Leever came through with his greatest season, compiling a 25-7 record, including seven shutouts, and a league-leading 2.06 ERA. During one stretch in July, the Pirates pitchers ran off a record six consecutive shutouts, with Leever pitching the second and sixth games of the streak. Although blessed with an exceptional curveball, Sam Leever believed his success lie elsewhere, as he told The Sporting News: "Most spectators have an exaggerated idea of the curve ball in pitching. They think the man in the box can send in all kinds of twists and thus fool the opposing batsman, but control-emphasize the word-and knowledge of the batter's weaknesses are much more important." Late in the 1903 season, Leever hurt his right shoulder in a trapshooting contest in Charleroi, Pennsylvania. Leever was an avid and accomplished trap shooter his entire life, but his injury dearly cost the Pirates in the 1903 World Series. Called "one of the best in the world today" in The Sporting News just prior to the series, Leever started the second game but removed himself after one inning. Six days later, he was asked to pitch the sixth game, and though he was able to finish, he was beaten 6-3. The Pirates fell to the upstart Bostons, in large part because of Leever's inability to pitch effectively. The Pirate pitching staff was further handicapped by Ed Doheny's late-season nervous breakdown, leaving Phillippe to start five of the eight World Series games. After the Series, Leever was accused by some writers of cowardice or, even worse, of giving less than his best effort in the second game. Ralph S. Davis, the Pittsburgh correspondent for The Sporting News, felt compelled to write a strong article in support of Leever, who was apparently still in considerable pain several weeks after the Series ended: "The charge that Leever 'laid' down is absurd in the extreme. There is not a more honest man in the game than Leever." When Sam reported to camp the following spring, he was not yet completely recovered from his injury. In his first regular season game in April, he argued a second inning balk call so strenuously that he was ejected and suspended for one week. Leever had been married in February to the former Margaret Molloy, and his new bride witnessed her famously taciturn husband's outburst and banishment. Her verdict: it sure looked like a balk. After winning eighteen games in 1904, Leever finished 20-5 and 22-7 the next two seasons, leading the league in winning percentage in 1905. Dogged by a sore arm that caused him to miss his turn in the rotation, Leever fell off to 14 wins in 1907, although with a career-best 1.66 ERA. By 1908 (15-7), he was pitching in relief half of the time. With two weeks remaining in the season, the Giants were leading the Cubs by four-and-a-half games and the Pirates by five. The gloomy Pirate players were talking one night, trying to convince themselves that they were still alive, when Sam, gloomier than most, offered to sell his World Series share for "a thin dime," and Fred Clarke and Vic Willis quickly handed him nickels. The Giants began losing and on October 4, the last scheduled day of the season, the Pirates met the Cubs at Chicago's West Side Park, with a win clinching no worse than a tie for the pennant. Sam Leever had his dime, but no longer had anything to gain monetarily from a Pirate victory, which would instead be accompanied by a lifetime of ribbing from his teammates. In the event, Mordecai Brown and the Cubs prevailed in the finale, 5-2. Leever was denied an opportunity to return to the World Series, but was spared a good deal of embarrassment. In his last two years with the Pirates, Leever pitched almost exclusively in relief, winning 14 and losing 6 in the two seasons. Prior to the 1911 season, the 38-year-old part-time pitcher was disappointed in the Pirates' tendered salary terms and refused to report to training camp. Barney Dreyfuss offered to sell Leever to a minor league team and to give him a share of the sale, but this only insulted Leever more, so he requested and received his release. He hooked on with Minneapolis, joining old teammate Rube Waddell, and won seven games to help lead the Millers to the American Association championship. After a year out of baseball, he was enticed to manage Covington in the Federal League in 1913, when it was an independent minor league. Deacon Phillippe managed the Pittsburgh entry in the same league. After the season, he hung up his uniform for good. Leever was an avid outdoorsman, and went on many long hunting trips during and after his baseball career, often with his friends Phillippe and Honus Wagner. Margaret once said that she knew spring training was near when Wagner came for his annual weeklong visit. Leever even made his own gunpowder, claiming it was better than any available on the open market. Leever was not only renowned for his serious demeanor; he was also known to be somewhat of a skinflint. Hugh Fullerton referred to him as "careful with his money" in an article written many years after Leever had retired. In 1924 Leever was startled to discover that he was dead, or believed to be so. As reported in The Sporting News, "he had a great deal of enjoyment out of reading his own obituary, and he appreciates all the nice things that were said about him, but he insists that he is not even half-dead. In fact, Sam says he never felt better in his life, and he has no thought whatever of cashing in." The misinformation was due to the passing of a distant relative with the same name. Sam and Margaret did not have any children. He retired to a seventy-acre farm, acquired with money he saved from his years in baseball, in Goshen, where he continued to teach school for many years. He was the postmaster in town for two terms, and had become one of the leading local citizens. He also maintained his passion for trap shooting, scoring of 99 (out of 100) as late as age 71. He eventually retired from farming and he and Margaret moved into her family's old place nearer to town. As Leever aged he apparently became rather crotchety. At least once he refused to attend a Christmas dinner with his wife's family because they were "a bunch of democrats." His house was not far from a baseball field, and old-timers in Goshen today remember hitting foul balls into his garden. If Sam got to the ball first, it is said, he would not give it back. Neighbors also remembered that he always wore a straw hat out of doors, and they were astonished when they saw him inside and realized that he was completely bald. Leever often attended ballgames in town, but he would rarely offer advice or talk much about his own great career. He died at home at age 81 on May 19, 1953.

NOTE:

An earlier version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D. C.: Brassey's Inc., 2004).

Sources

Obituary. Unknown Ohio newspaper, May 5, 1953.

Obituary. The Sporting News, May 27, 1953.

"Dope Sheet" from Sam Leever's file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

DeValeria, Dennis and Jeanne Burke. Honus Wagner. Henry Holt, 1995.

Erardi , John. "Goshen Cemetary Holds Hidden Baseball Treasure."

The Cincinnati Enquirer, January 14, 2001.

Fullerton, Hugh. "The Sad Plight of Sam Leever."

Liberty Magazine. July 28, 1928.

Lieb, Fred. The Pittsburgh Pirates. Putnam, 1948.

The Sporting News. September-November, 1903; August 16, 1902; November 24, 1924.

With piercing blue eyes and brown hair that was thinning even early in his baseball career, Sam Leever was known as "The Goshen Schoolmaster," as much for his appearance and serious disposition as for his off-season disposition. Leever relied on his exceptional curveball and control to compile a record of 194-100, for a .660 winning percentage, the ninth highest in baseball history. In an era when pitchers were listed in the newspapers each week according to their winning percentages, the oft-injured right-hander was the National League's "leading pitcher" in 1901, 1903, and 1905. The fourth of Edward and Amerideth Leever's eight children, Samuel Leever was born on December 23, 1871, on a farm in Goshen, Ohio, about twenty miles northeast of Cincinnati. Like many of their neighbors, the Leevers were of Pennsylvania German heritage. After graduating from Goshen High School, Leever taught there for seven years before he signed his first baseball contract at the advanced age of 25. A star pitcher for several years on club teams in southwestern Ohio, Leever was a teammate of future major leaguer Kid Elberfield with the local Norwood Maroons. He taught school during the week and pitched on Sundays. A big strong right-hander with an exceptional curveball, Leever was not signed sooner likely because he was not a hard thrower-he relied more on control and the movement of his pitches. An oft-told legend, undoubtedly apocryphal, claimed that Barney Dreyfuss, then the owner of the Louisville Colonels, discovered Leever while he was playing "Anthony Over," a game that required tossing a ball over a barn to a friend. Leever was apparently able to curve the ball around the barn instead. His first professional season was 1897 with Richmond of the Atlantic League, where he won 20 games and led the league in strikeouts. Pittsburgh purchased his contract for 1898, but when he reported with a sore arm the club sent him back to Richmond, where he won 14 more games and helped lead his team to the league championship. His success earned him a recall to Pittsburgh for the tail end of the season, and he won his only decision. As an 1899 rookie, Leever pitched in a league-leading 51 games and 379 innings, and compiled a record of 21-23. Manager Patsy Donovan not only let him complete 35 games, Leever also led the league by finishing 11 games for other pitchers and by saving (as retroactively calculated) three games. Though a sore right arm nagged him occasionally throughout his career, Leever never had another losing season, and never again had an ERA as high as 3.00. During the years 1900-1902, with an exceptionally deep and talented pitching staff at his disposal, manager Fred Clarke used what amounted to a five-man rotation most of the time, thus preventing any of his great pitchers from accumulating huge win totals. Leever won 44 and lost 25 over these three years, leading the league in winning percentage (.737) in 1901. Following the 1902 seasons, fellow pitching stalwarts Jack Chesbro and Jesse Tannehill jumped to the New York Highlanders of the American League, and Leever and his good friend Deacon Phillippe were accordingly called on to carry a much larger burden in 1903. Leever came through with his greatest season, compiling a 25-7 record, including seven shutouts, and a league-leading 2.06 ERA. During one stretch in July, the Pirates pitchers ran off a record six consecutive shutouts, with Leever pitching the second and sixth games of the streak. Although blessed with an exceptional curveball, Sam Leever believed his success lie elsewhere, as he told The Sporting News: "Most spectators have an exaggerated idea of the curve ball in pitching. They think the man in the box can send in all kinds of twists and thus fool the opposing batsman, but control-emphasize the word-and knowledge of the batter's weaknesses are much more important." Late in the 1903 season, Leever hurt his right shoulder in a trapshooting contest in Charleroi, Pennsylvania. Leever was an avid and accomplished trap shooter his entire life, but his injury dearly cost the Pirates in the 1903 World Series. Called "one of the best in the world today" in The Sporting News just prior to the series, Leever started the second game but removed himself after one inning. Six days later, he was asked to pitch the sixth game, and though he was able to finish, he was beaten 6-3. The Pirates fell to the upstart Bostons, in large part because of Leever's inability to pitch effectively. The Pirate pitching staff was further handicapped by Ed Doheny's late-season nervous breakdown, leaving Phillippe to start five of the eight World Series games. After the Series, Leever was accused by some writers of cowardice or, even worse, of giving less than his best effort in the second game. Ralph S. Davis, the Pittsburgh correspondent for The Sporting News, felt compelled to write a strong article in support of Leever, who was apparently still in considerable pain several weeks after the Series ended: "The charge that Leever 'laid' down is absurd in the extreme. There is not a more honest man in the game than Leever." When Sam reported to camp the following spring, he was not yet completely recovered from his injury. In his first regular season game in April, he argued a second inning balk call so strenuously that he was ejected and suspended for one week. Leever had been married in February to the former Margaret Molloy, and his new bride witnessed her famously taciturn husband's outburst and banishment. Her verdict: it sure looked like a balk. After winning eighteen games in 1904, Leever finished 20-5 and 22-7 the next two seasons, leading the league in winning percentage in 1905. Dogged by a sore arm that caused him to miss his turn in the rotation, Leever fell off to 14 wins in 1907, although with a career-best 1.66 ERA. By 1908 (15-7), he was pitching in relief half of the time. With two weeks remaining in the season, the Giants were leading the Cubs by four-and-a-half games and the Pirates by five. The gloomy Pirate players were talking one night, trying to convince themselves that they were still alive, when Sam, gloomier than most, offered to sell his World Series share for "a thin dime," and Fred Clarke and Vic Willis quickly handed him nickels. The Giants began losing and on October 4, the last scheduled day of the season, the Pirates met the Cubs at Chicago's West Side Park, with a win clinching no worse than a tie for the pennant. Sam Leever had his dime, but no longer had anything to gain monetarily from a Pirate victory, which would instead be accompanied by a lifetime of ribbing from his teammates. In the event, Mordecai Brown and the Cubs prevailed in the finale, 5-2. Leever was denied an opportunity to return to the World Series, but was spared a good deal of embarrassment. In his last two years with the Pirates, Leever pitched almost exclusively in relief, winning 14 and losing 6 in the two seasons. Prior to the 1911 season, the 38-year-old part-time pitcher was disappointed in the Pirates' tendered salary terms and refused to report to training camp. Barney Dreyfuss offered to sell Leever to a minor league team and to give him a share of the sale, but this only insulted Leever more, so he requested and received his release. He hooked on with Minneapolis, joining old teammate Rube Waddell, and won seven games to help lead the Millers to the American Association championship. After a year out of baseball, he was enticed to manage Covington in the Federal League in 1913, when it was an independent minor league. Deacon Phillippe managed the Pittsburgh entry in the same league. After the season, he hung up his uniform for good. Leever was an avid outdoorsman, and went on many long hunting trips during and after his baseball career, often with his friends Phillippe and Honus Wagner. Margaret once said that she knew spring training was near when Wagner came for his annual weeklong visit. Leever even made his own gunpowder, claiming it was better than any available on the open market. Leever was not only renowned for his serious demeanor; he was also known to be somewhat of a skinflint. Hugh Fullerton referred to him as "careful with his money" in an article written many years after Leever had retired. In 1924 Leever was startled to discover that he was dead, or believed to be so. As reported in The Sporting News, "he had a great deal of enjoyment out of reading his own obituary, and he appreciates all the nice things that were said about him, but he insists that he is not even half-dead. In fact, Sam says he never felt better in his life, and he has no thought whatever of cashing in." The misinformation was due to the passing of a distant relative with the same name. Sam and Margaret did not have any children. He retired to a seventy-acre farm, acquired with money he saved from his years in baseball, in Goshen, where he continued to teach school for many years. He was the postmaster in town for two terms, and had become one of the leading local citizens. He also maintained his passion for trap shooting, scoring of 99 (out of 100) as late as age 71. He eventually retired from farming and he and Margaret moved into her family's old place nearer to town. As Leever aged he apparently became rather crotchety. At least once he refused to attend a Christmas dinner with his wife's family because they were "a bunch of democrats." His house was not far from a baseball field, and old-timers in Goshen today remember hitting foul balls into his garden. If Sam got to the ball first, it is said, he would not give it back. Neighbors also remembered that he always wore a straw hat out of doors, and they were astonished when they saw him inside and realized that he was completely bald. Leever often attended ballgames in town, but he would rarely offer advice or talk much about his own great career. He died at home at age 81 on May 19, 1953.

NOTE:

An earlier version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D. C.: Brassey's Inc., 2004).

Sources

Obituary. Unknown Ohio newspaper, May 5, 1953.

Obituary. The Sporting News, May 27, 1953.

"Dope Sheet" from Sam Leever's file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

DeValeria, Dennis and Jeanne Burke. Honus Wagner. Henry Holt, 1995.

Erardi , John. "Goshen Cemetary Holds Hidden Baseball Treasure."

The Cincinnati Enquirer, January 14, 2001.

Fullerton, Hugh. "The Sad Plight of Sam Leever."

Liberty Magazine. July 28, 1928.

Lieb, Fred. The Pittsburgh Pirates. Putnam, 1948.

The Sporting News. September-November, 1903; August 16, 1902; November 24, 1924.