The Great Wigwag Scheme of 1909 By Mike Lynch

It was Sept. 25, 1909 and the New York Highlanders were going nowhere fast. But things were about to get better fast, thanks to a notable bit of baseball chicanery.

Heading into a twin-bill against the first-place and eventual American League champion Detroit Tigers, New York was fifth and 23 games behind with a 68-73 record. Led by second baseman Frank LaPorte, outfielders Clyde Engle and Ray Demmitt and first baseman Hal Chase, the team’s offense was in the middle of the pack, scoring 3.86 runs per game.

Though the pitching staff boasted a starter in Joe Lake, who posted a 1.88 earned run average and part-time starter Jack Quinn, who pitched to a 1.97 ERA, the unit as a whole ranked next to last in the league in runs allowed per game at 3.84.

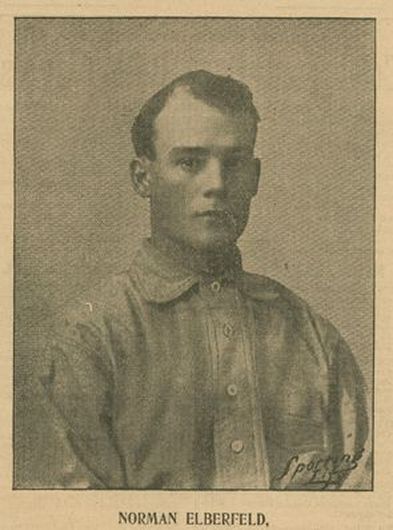

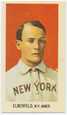

The Highlanders, who officially became the Yankees upon moving from Hilltop Park into the Polo Grounds in 1913, finished the season a week later, still in fifth place at 74-77 and 23 1/2 games out of first. But considering they had suffered through the worst season in franchise history in 1908, going 51-103 under managers Clark Griffith (24-32) and Kid Elberfeld (27-71), the 1909 campaign was a success. Plus, the Highlanders reached a half-million in attendance for the first time, pulling in 501,000 paying customers.

Known as “The Tabasco Kid” for his demeanor — he was once called the “dirtiest, scrappiest, most pestiferous, most rambunctious ballplayer that ever stood on spikes” — Elberfeld angered and alienated teammates, who questioned his managerial qualifications and eventually revolted. That he was tabbed to manage the squad was odd considering he’d been suspended by owner Frank Farrell in 1907 for “indifferent work in the field and at the bat.”

Under Elberfeld the team went 7-39 from late June to mid-August, prompting one writer to opine, “There was never a worse case of sulky laying down than Elberfeld’s last year. Mr. Farrell is reaping what he sowed.”

Farrell replaced Elberfeld with George Stallings, a 41-year-old former National League player and manager who guided the 1901 Tigers to a 74-61 record and third-place finish in their inaugural season. Stallings began his career in 1890 with the Brooklyn Bridegrooms and went 0-for-11 in four games, then managed the Philadelphia Phillies in 1897 and part of 1898. The Phils went 55-77 and finished 10th in a 12 team league in ‘97 then were 19-27 under Stallings in ‘98 before Bill Shettsline took over.

Stallings was an intelligent man, having graduated from Virginia Military Institute in 1886 and studied medicine in Baltimore for a year before turning to professional baseball. Johnny Evers, who played for Stallings from 1914 to 1917, once said, “Mr. Stallings knows more baseball than any man with whom I have ever come in contact during my connection with the game.” This opinion gained further support in 1914 when Stallings’ “Miracle” Boston Braves went from last place on July 4 to win the National League pennant and sweep Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series.

Boston second baseman Johnny Evers is shown here with manager George Stallings in the Braves dugout in 1914. The Braves went from last to first during the 1914 season and beat the Philadelphia Athletics to capture the World Championship.

In addition to his time in the majors, Stallings had minor league managerial experience, having piloted teams in the Southern Association, Western League and Eastern League and led the Class A Buffalo Bisons to pennants in 1904 and 1906.

Much like Elberfeld before him, Stallings was a controversial choice in New York. American League president Ban Johnson had effectively run Stallings out of the league in 1901 when he accused the Detroit skipper of trying to sell Tigers interests to the National League. Stallings refuted the claim, correctly citing that Johnson owned 51 percent of each club’s stock to prevent it from leaving the circuit, and he couldn’t sell anything even if he wanted to.

Upon his hiring by the Highlanders, Sporting Life magazine wrote, “In securing George T. Stallings as team manager, President Farrell has made the best possible move, present conditions and availability considered. Stallings has not only wide experience but all other qualities that go to make a successful baseball leader.”

The team got off to a decent enough start and on May 31 was in third place, only 4 1/2 games behind Detroit. But the wheels fell off in June. After jumping into second place on June 7, the Highlanders won only seven of their next 23 contests and fell to fifth place with a record of 29-31.

Interestingly, it was around that same time that Sporting Life wrote about Stallings’ opinion of Hilltop Park. “If there’s something about a grounds, such as a background to affect the batting eye, home players always figure that they get the worst of it, but George Stallings doesn’t agree with this view.”

His players might have been on to something, though. They scored 58 runs in their first eight home games through May, an average of 7.3, then managed only 3.9 runs a game at home in June. July wasn’t much better as the team struggled to a 14-19 record and dropped to sixth place with a 43-50 mark, and August was downright pathetic. Not only did the Highlanders lose 16 of 27 to fall to 54-66, but they averaged only 3.1 runs a game at home and 2.8 on the road.

On Aug. 31, the team was mired in sixth place, 23 games out of first, but it suddenly heated up in September, pushing across 4.6 runners a game at home. The Highlanders went 17-10 to pull within five games of .500, but not without some controversy.

On Sept. 26, reports surfaced that the Yankees were stealing signals from opposing catchers and that was the reason for their sudden offensive surge. Tigers manager Hughie Jennings had been tipped off to a “wigwag” scheme, so dubbed by the Chicago Tribune while his team was in Washington playing the Senators.

Washington skipper Joe Cantillon shared his suspicions about the Highlanders’ shenanigans, and the Tigers’ manager decided to investigate upon his team’s arrival in New York on Sept. 25. Jennings sent pitcher Bill Donovan to Hilltop Park’s outfield fence to take a look around, but the hurler could find nothing suspicious. Unsatisfied, Jennings dispatched team trainer Harry Tuthill to take a closer look.

During the third inning of the first game of the doubleheader, Tuthill discovered that the crossbar in the “H” of a Young’s Hats sign in center field was changing colors. Tuthill climbed the outfield fence and discovered a small enclosure covered in barbed wire where a man was sitting with binoculars and using a lever to signal to New York batters whether a straight ball or curveball was coming.

”The operator, seeing [Tuthill] coming, dropped his paraphernalia and bolted,” reported the Tribune. The Tigers’ trainer broke the lever, confiscated the binoculars and turned over the evidence to Jennings, who in turn handed over the goods to New York officials.

Glenn Stout writes in “Yankees Century” that earlier in the season Stallings had “rented an apartment opposite Hilltop Park that provided a good view of home plate” and had “installed a spotter in the apartment armed with a pair of field glasses” who would signal Highlanders hitters with a mirror.

Late in the 1909 season, the Highlanders were accused of stealing signs from the Young’s Hat and O.F.C. Rye signs hanging from the outfield wall at Hilltop Park.

It was also reported that signals were coming from an O.F.C. Whiskey sign, wherein the “O” served to indicate what pitches were coming. Regardless, it appeared that the Highlanders had something up their collective sleeves.

Tuthill reportedly recognized the spy, but he and Jennings chose not to file a formal report because they hadn’t been harmed by the “signal-tipping bureau.” But on Oct. 2, Ban Johnson demanded that Tuthill tell him everything he knew or risk expulsion from the league.

Two weeks later, J. Ed Grillo reported in the Washington Post that Johnson had enough evidence to “insist that the New York club sever its contract” with Stallings.

”Of course, he will be given a chance to defend himself,” Grillo wrote, “but with the abundance of evidence which the American League chief has gathered, it is not likely that there will be anything produced to show that Stallings was ignorant of what was going on between the centerfield fences.”

In the end, it was Johnson who “whitewashed” the whole affair and let New York off the hook. ”Had it been a weak club which was involved in the affair, he would probably have meted out some banishments from the game,” wrote Grillo, “but the New York club is too strong, and he did not dare take action.”

The official statement read: “Whereas charges having been printed in the public press to the effect that during the past season a sign-tipping bureau was operated on the grounds of the New York American League ball club; and whereas the board of directors of the American League has considered carefully all the evidence before it to the existence of such a bureau; therefore, be it resolved, that in the opinion of the board, the New York club is free from all complicity in such a tipping affair; be it further resolved, that it is the sense of the board that any manager or official proved guilty of operating a sign-tipping bureau should be barred from baseball for all time.”

Despite speculation that Highlanders manager George Stallings had orchestrated a way to steal opposing teams’ signs, there was no rule at the time which prohibited sign stealing in the manner that he was being accused. Following the 1909 season, the AL Board of Directors ruled that any team official found stealing signs in the future would be “barred from baseball for all time.”

Heading into a twin-bill against the first-place and eventual American League champion Detroit Tigers, New York was fifth and 23 games behind with a 68-73 record. Led by second baseman Frank LaPorte, outfielders Clyde Engle and Ray Demmitt and first baseman Hal Chase, the team’s offense was in the middle of the pack, scoring 3.86 runs per game.

Though the pitching staff boasted a starter in Joe Lake, who posted a 1.88 earned run average and part-time starter Jack Quinn, who pitched to a 1.97 ERA, the unit as a whole ranked next to last in the league in runs allowed per game at 3.84.

The Highlanders, who officially became the Yankees upon moving from Hilltop Park into the Polo Grounds in 1913, finished the season a week later, still in fifth place at 74-77 and 23 1/2 games out of first. But considering they had suffered through the worst season in franchise history in 1908, going 51-103 under managers Clark Griffith (24-32) and Kid Elberfeld (27-71), the 1909 campaign was a success. Plus, the Highlanders reached a half-million in attendance for the first time, pulling in 501,000 paying customers.

Known as “The Tabasco Kid” for his demeanor — he was once called the “dirtiest, scrappiest, most pestiferous, most rambunctious ballplayer that ever stood on spikes” — Elberfeld angered and alienated teammates, who questioned his managerial qualifications and eventually revolted. That he was tabbed to manage the squad was odd considering he’d been suspended by owner Frank Farrell in 1907 for “indifferent work in the field and at the bat.”

Under Elberfeld the team went 7-39 from late June to mid-August, prompting one writer to opine, “There was never a worse case of sulky laying down than Elberfeld’s last year. Mr. Farrell is reaping what he sowed.”

Farrell replaced Elberfeld with George Stallings, a 41-year-old former National League player and manager who guided the 1901 Tigers to a 74-61 record and third-place finish in their inaugural season. Stallings began his career in 1890 with the Brooklyn Bridegrooms and went 0-for-11 in four games, then managed the Philadelphia Phillies in 1897 and part of 1898. The Phils went 55-77 and finished 10th in a 12 team league in ‘97 then were 19-27 under Stallings in ‘98 before Bill Shettsline took over.

Stallings was an intelligent man, having graduated from Virginia Military Institute in 1886 and studied medicine in Baltimore for a year before turning to professional baseball. Johnny Evers, who played for Stallings from 1914 to 1917, once said, “Mr. Stallings knows more baseball than any man with whom I have ever come in contact during my connection with the game.” This opinion gained further support in 1914 when Stallings’ “Miracle” Boston Braves went from last place on July 4 to win the National League pennant and sweep Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series.

Boston second baseman Johnny Evers is shown here with manager George Stallings in the Braves dugout in 1914. The Braves went from last to first during the 1914 season and beat the Philadelphia Athletics to capture the World Championship.

In addition to his time in the majors, Stallings had minor league managerial experience, having piloted teams in the Southern Association, Western League and Eastern League and led the Class A Buffalo Bisons to pennants in 1904 and 1906.

Much like Elberfeld before him, Stallings was a controversial choice in New York. American League president Ban Johnson had effectively run Stallings out of the league in 1901 when he accused the Detroit skipper of trying to sell Tigers interests to the National League. Stallings refuted the claim, correctly citing that Johnson owned 51 percent of each club’s stock to prevent it from leaving the circuit, and he couldn’t sell anything even if he wanted to.

Upon his hiring by the Highlanders, Sporting Life magazine wrote, “In securing George T. Stallings as team manager, President Farrell has made the best possible move, present conditions and availability considered. Stallings has not only wide experience but all other qualities that go to make a successful baseball leader.”

The team got off to a decent enough start and on May 31 was in third place, only 4 1/2 games behind Detroit. But the wheels fell off in June. After jumping into second place on June 7, the Highlanders won only seven of their next 23 contests and fell to fifth place with a record of 29-31.

Interestingly, it was around that same time that Sporting Life wrote about Stallings’ opinion of Hilltop Park. “If there’s something about a grounds, such as a background to affect the batting eye, home players always figure that they get the worst of it, but George Stallings doesn’t agree with this view.”

His players might have been on to something, though. They scored 58 runs in their first eight home games through May, an average of 7.3, then managed only 3.9 runs a game at home in June. July wasn’t much better as the team struggled to a 14-19 record and dropped to sixth place with a 43-50 mark, and August was downright pathetic. Not only did the Highlanders lose 16 of 27 to fall to 54-66, but they averaged only 3.1 runs a game at home and 2.8 on the road.

On Aug. 31, the team was mired in sixth place, 23 games out of first, but it suddenly heated up in September, pushing across 4.6 runners a game at home. The Highlanders went 17-10 to pull within five games of .500, but not without some controversy.

On Sept. 26, reports surfaced that the Yankees were stealing signals from opposing catchers and that was the reason for their sudden offensive surge. Tigers manager Hughie Jennings had been tipped off to a “wigwag” scheme, so dubbed by the Chicago Tribune while his team was in Washington playing the Senators.

Washington skipper Joe Cantillon shared his suspicions about the Highlanders’ shenanigans, and the Tigers’ manager decided to investigate upon his team’s arrival in New York on Sept. 25. Jennings sent pitcher Bill Donovan to Hilltop Park’s outfield fence to take a look around, but the hurler could find nothing suspicious. Unsatisfied, Jennings dispatched team trainer Harry Tuthill to take a closer look.

During the third inning of the first game of the doubleheader, Tuthill discovered that the crossbar in the “H” of a Young’s Hats sign in center field was changing colors. Tuthill climbed the outfield fence and discovered a small enclosure covered in barbed wire where a man was sitting with binoculars and using a lever to signal to New York batters whether a straight ball or curveball was coming.

”The operator, seeing [Tuthill] coming, dropped his paraphernalia and bolted,” reported the Tribune. The Tigers’ trainer broke the lever, confiscated the binoculars and turned over the evidence to Jennings, who in turn handed over the goods to New York officials.

Glenn Stout writes in “Yankees Century” that earlier in the season Stallings had “rented an apartment opposite Hilltop Park that provided a good view of home plate” and had “installed a spotter in the apartment armed with a pair of field glasses” who would signal Highlanders hitters with a mirror.

Late in the 1909 season, the Highlanders were accused of stealing signs from the Young’s Hat and O.F.C. Rye signs hanging from the outfield wall at Hilltop Park.

It was also reported that signals were coming from an O.F.C. Whiskey sign, wherein the “O” served to indicate what pitches were coming. Regardless, it appeared that the Highlanders had something up their collective sleeves.

Tuthill reportedly recognized the spy, but he and Jennings chose not to file a formal report because they hadn’t been harmed by the “signal-tipping bureau.” But on Oct. 2, Ban Johnson demanded that Tuthill tell him everything he knew or risk expulsion from the league.

Two weeks later, J. Ed Grillo reported in the Washington Post that Johnson had enough evidence to “insist that the New York club sever its contract” with Stallings.

”Of course, he will be given a chance to defend himself,” Grillo wrote, “but with the abundance of evidence which the American League chief has gathered, it is not likely that there will be anything produced to show that Stallings was ignorant of what was going on between the centerfield fences.”

In the end, it was Johnson who “whitewashed” the whole affair and let New York off the hook. ”Had it been a weak club which was involved in the affair, he would probably have meted out some banishments from the game,” wrote Grillo, “but the New York club is too strong, and he did not dare take action.”

The official statement read: “Whereas charges having been printed in the public press to the effect that during the past season a sign-tipping bureau was operated on the grounds of the New York American League ball club; and whereas the board of directors of the American League has considered carefully all the evidence before it to the existence of such a bureau; therefore, be it resolved, that in the opinion of the board, the New York club is free from all complicity in such a tipping affair; be it further resolved, that it is the sense of the board that any manager or official proved guilty of operating a sign-tipping bureau should be barred from baseball for all time.”

Despite speculation that Highlanders manager George Stallings had orchestrated a way to steal opposing teams’ signs, there was no rule at the time which prohibited sign stealing in the manner that he was being accused. Following the 1909 season, the AL Board of Directors ruled that any team official found stealing signs in the future would be “barred from baseball for all time.”