Deadball Stars of the American League by David Jones, ed.

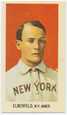

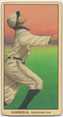

Kid Elberfeld

This article was written by Terry Simpkins.

Kid Elberfeld, called "the dirtiest, scrappiest, most pestiferous, most rantankerous [sic], most rambunctious ball player that ever stood on spikes" for his vicious arguments on the diamond, patterned his combative style after that of his favorite team, the Baltimore Orioles of the mid-1890s. He believed, like those Oriole players, that an umpire should be kept in his place, and that what happened behind an arbiter's back was none of his business. But, when Elberfeld kept his volatile temper in check, he was also an "ideal infielder--full of ginger." Called by George Stallings one of the two best shortstops in baseball, his throwing arm was "cyclonic," and, though only 5'7," 158 lbs., he was fearless in turning the double play. Not surprisingly, he was frequently spiked, and by 1907 wore a whalebone shin guard on his right leg for protection. He was also one of the best hitting shortstops of his day, with a career .271 average, and a master at getting hit by close pitches. He perfected the art of angling his body in toward the plate, holding his arms in such as way as to take only a glancing blow while simultaneously appearing to make an honest attempt to avoid the pitch, and then, for effect, shouting and gesticulating at the pitcher. He became so adept at this that he still ranks 13th on the career hit by pitch list, with 165.

Norman Arthur Elberfeld was born on April 13, 1875, in Pomeroy, Ohio, on the Ohio River, between Cincinnati and Pittsburgh. His parents, Philip Elberfeld, a shoe merchant, and Katherine Eiselstein, were German immigrants who had settled in Meigs County, Ohio in the mid-nineteenth century. Norman was the tenth of eleven children--six boys and five girls--though the youngest child died when Kid was six years old. In 1878 the family moved to Cincinnati. Called "Kid" from his earliest days, Elberfeld had only a few years of formal schooling, and as a youngster played mainly hockey and baseball. From 1892 to 1894 he captained local baseball teams in the Norwood and Bond Hill neighborhoods of Cincinnati and played nearly every position, including catcher. In 1895, Elberfeld joined an independent team in Clarksville, Tennessee, managed and partly owned by former major leaguer Billy Earle.

Elberfeld's first professional job came the next season when he and Earle joined the Dallas Navigators of the Texas Association. A pre-season contract dispute with Montgomery was settled in Dallas' favor, but Elberfeld's season with the Navigators ended abruptly in May due to a leg injury. Jumping his contract with Dallas (possibly under the influence of Earle, who left at the same time), he recovered enough to latch on with a club in Lexington, Kentucky, where Jake Wells of the Richmond Bluebirds spotted him. Elberfeld played with Richmond of the Atlantic League in 1897. His .335 batting average and 45 stolen bases attracted the attention of the Philadelphia Phillies, who purchased his contract in September.

Elberfeld didn't play for Philadelphia in 1897, and his 1898 major league debut was delayed by knee injuries caused by a spring training bathtub fall. Finally, on May 30, he started the first game of a doubleheader against Louisville at third base and belted two doubles, got hit by a pitch, and committed two errors in the field. He quickly became a favorite with the Philadelphia fans, but poor fielding and a penchant for interfering with opposing runners left the local writers less impressed. One wrote: "Elberfeld might as well learn now that Philadelphia ballcranks will not stand for his minor league methods. What we want [are] ball players, not toughs." He played only 14 games for Philadelphia, and, though presented with a gold watch during a late-June game at Cincinnati by his hometown fans, was sold to the Western League Detroit Tigers in July, where he was ejected and fined in one of his first games. He finished the year with a lowly .238 average.

In 1899, Elberfeld hit .308 and stole 23 bases, earning him another chance in the majors. The Cincinnati Reds purchased his contract in August, but he injured his back, batted and fielded poorly, and was generally overshadowed by another rookie acquired around the same time, Sam Crawford. He jumped back to Detroit in 1900, where, as the "most aggressive" player on the "most aggressive and scrappiest" team in the newly renamed American League, he was ejected from three games during one eight-game stretch in June. Though he batted only .263, he led all shortstops with an astonishing average of over seven successful chances per game. He also married Emily Grace Catlow on October 10, and settled in Chattanooga, where he raised chickens on his farm during off seasons, and, later, tended to his apple orchard.

Elberfeld remained with Detroit for the next 2½ years. In 1901, as the Tigers staked their claim to major league status, he batted .308 with 11 triples and three home runs, all of which would remain his major league career highs. Near the end of the 1902 season, New York Giants' owner John T. Brush and manager John McGraw attempted to beef up their last place team by signing several Detroit players, and reportedly signed Elberfeld to a two-year contract for $4500 per year. McGraw's personality appealed to Elberfeld. "McGraw always liked me," Elberfeld said. "I played his aggressive style of ball. And I would have liked to have played for him." But the 1903 peace agreement returned Elberfeld to Detroit, and, when Edward Barrow was suddenly named to replace suicide-victim Win Mercer as new Detroit manager, Barrow inherited an unhappy shortstop. Though Elberfeld started fast, batting .431 after the first three weeks of the season, his hitting soon tailed off and his fielding was shoddy. On June 2, Barrow fined and suspended him for "loaferish conduct," suspecting Elberfeld of playing poorly to force a trade to the St. Louis Browns. Eight days later, Barrow did trade him, not to St. Louis, but to the New York Highlanders.

The move nearly derailed the nascent peace treaty between the leagues. Brush, opposed to peace in the first place, viewed the trade as an attempt by AL President Ban Johnson to siphon fans from the Giants. Brush badgered NL President Harry Pulliam into declaring that Johnson had violated the "spirit if not the letter" of the treaty and persuaded Pulliam to let McGraw use George Davis--then the subject of a dispute between the Giants and the Chicago White Sox--at shortstop. The case dragged on for weeks. In the meantime, Elberfeld got himself charged with disorderly conduct and fined for throwing a bottle (some reports say a knife) at a hotel waiter. Ultimately, the other NL owners decided they couldn't afford another interleague war, and on July 20 repudiated Brush's position. One of Elberfeld's career highlights came a short while later, on August 1, in a 3-2 victory Highlander victory over Philadelphia ace Rube Waddell. Elberfeld made all four New York hits and drove in all three runs as Waddell struck out 13 New Yorkers. It was after his arrival in New York, too, that sportswriter Sam Crane dubbed Elberfeld "Tabasco" Kid, referring to Elberfeld's now infamous temper and "peppery" style of play.

Over the next three years with New York, Elberfeld solidified his reputation as one of the best hitting shortstops in baseball. From 1904 to 1906, he had the highest batting (.275) and on-base-plus-slugging (.688) percentages of any shortstop in the American League, and second in the majors only to Honus Wagner. But injuries and suspensions continued to dog him; the Highlanders might have won pennants in 1904 and 1906 had Elberfeld not missed 89 games during those years. In late 1906 he also had two memorable run-ins with umpire Silk O'Loughlin. The first, on August 8, occurred when Elberfeld was denied first base by after being hit by a pitch, prompting him to menace the umpire with a bat. Then, on September 3, the two went at it again in a brawl described by the New York Times as "one of the most disgraceful scenes ever witnessed on a baseball field." The Highlanders were in a close pennant race with Chicago, and when Elberfeld was suspended for only a total of eight games by President Johnson, some viewed it as an act of favoritism toward the Highlanders.

Elberfeld's last years in New York were difficult. He feuded with teammates Wid Conroy, Jimmy Williams, Ira Thomas, and Hal Chase, and, in July 1907, was suspended by Highlander owner Frank Farrell for what the New York Times called "indifferent work in the field and at the bat." Elberfeld, harboring unrealized managerial aspirations, again sought to force a trade (this time with Washington) through sulking and lackadaisical play. When it was announced between games of a July 26 doubleheader that Conroy would replace Elberfeld, 8,000 fans greeted the news with "tumultuous" applause. After Elberfeld apologized to manager Clark Griffith, Farrell lifted the suspension on August 15 and, before 1908, Elberfeld was even offered a contract for $2700--with a $1000 bonus if he behaved himself.

On May 1, 1908, with the New Yorkers tied for first place, Elberfeld was severely spiked by Washington outfielder Bob Ganley, essentially ending Elberfeld's season. The team continued to play well without him through May, but won only seven games during June. On June 25, Farrell finally forced Griffith to resign, and Elberfeld got his chance to be manager. His tenure was a disaster. New York lost 15 of their next 18 games and the Washington Post soon quoted an unnamed Highlander saying: "We are ... playing under the direction of a crazy man. It won't take Elberfeld more than two weeks to make us the most demoralized ball team that the American League has ever known. He thinks he is a manager, but he can't convince any one but himself that he has the first qualification for the place. It's a joke." But Elberfeld himself apparently did harbor doubts about his qualifications; some years later Baseball Magazine reported that he wouldn't select the team's starting pitchers without first consulting his wife. Regardless of who picked the pitchers, the Highlanders sank to last place, Chase jumped the team in early September, and Elberfeld's sole stint as a major league manager ended with a dismal 27-71 record.

Though replaced by George Stallings as manager after the season, Elberfeld remained with the team, reluctantly, as a player in 1909; his nasty reputation, high salary, and history of injuries made him difficult to trade. His battered legs forced him to play more at third base, a familiar position from his early days and one for which he was well-suited because of his strong arm. Rusty from his long lay off, Elberfeld batted only .237 that year, but showed enough life to enable Stallings to sell him to Washington in December. The next spring, he began coaching young players from D.C.-area town and high school teams, an occupation that would dominate his activities after his playing days ended. "[Kids are] the future players, future fans, and future owners," he later said. "We need to teach them the game from the time they are old enough to swing a bat."

Elberfeld remained with Washington for two years, and manager Jimmy McAleer twice selected Elberfeld to play on post-season "all-star" teams formed to keep the pennant-winning A's sharp for their upcoming World Series appearances. In 1911, Elberfeld played through ankle, hip, and back injuries. Though he batted a solid .272 and posted a career high .405 OBP, in 1912 the new Nats manager Griffith was determined to go with younger players, and, prior to the season, Elberfeld was sold to Montgomery of the

Southern Association. He batted .260 in 78 games forthe Rebels, then moved on to the Chattanooga Lookouts in 1913 as player-manager where he batted .332 in 94 games. He was then hired to manage New Orleans, but after a change in team ownership left him jobless, Brooklyn signed him as a coach and utility player. Elberfeld played his final major league game on September 24, 1914, entering the game, ironically, as a late-inning defensive replacement when starting shortstop Dick Egan was ejected for arguing a call.

His big league days over, Elberfeld forged a second career as a minor league player and manager, primarily in the Southern Association. He spent three more years at Chattanooga, taking over as manager in July 1915. In 1918, he managed Little Rock, playing sporadically, and worked briefly at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, as a Y.M.C.A. director, teaching soldiers to throw hand grenades like baseballs. Two years later he managed Little Rock to a league championship, though they were upset by the Class B Texas League champions Fort Worth in the post-season series. He stayed with Little Rock for four more seasons, followed by stints in Mobile, Chattanooga and Little Rock again, and Springfield in the Western Association. After scouting for Little Rock and Atlanta, he finished his minor league managerial career in 1936 with the Fulton (Kentucky) Eagles in the Class D Kitty League, even appearing in one last game as a 61-year-old pinch hitter.

Though an utter failure as a leader of mature major league players, Elberfeld was highly successful working with younger athletes. He discovered or helped develop many major league players, including Casey Stengel, Travis Jackson, Bill Terry, Cecil Travis, and Jim Turner, though his influence wasn't uniformly positive--Burleigh Grimes blamed his own notoriously bad temper on his early exposure to Elberfeld. Beginning in the 1920s, he ran or participated in baseball schools throughout the South, even managing the female pitcher Jackie Mitchell on his 1931 barnstorming team, the Lookout Juniors. He had a lot of experience tutoring female athletes; of his six children, five were girls, and during the mid-1920s they competed as boxers, held state and national amateur championships in tennis and swimming, and even formed a basketball team around Chattanooga called the "Elberfeld Sisters."

In the early 1940s, Elberfeld ran annual baseball camps sponsored by Coca-Cola in Minden, Louisiana. He would regale the boys with reminiscences of his career and show off the scars crisscrossing his legs. Though patient with his more uncoordinated charges, traces of the "Tabasco Kid" of old still remained: he called them "rock" or "hardhead" when they botched a play, and passed along tips on the finer points of bench jockeying.

Early in 1944, Elberfeld caught a cold and, on January 13, died of pneumonia at Erlanger Hospital in Chattanooga. He was buried in Chattanooga Memorial Park. Three years later, on July 6, 1947, Elberfeld's grandson unveiled a plaque at Engel Stadium in Chattanooga. Without a trace of irony, it read, "In memoriam, Norman Elberfeld ... a sportsman and a friend ... dedicated 1947 by his many friends in baseball," honoring not his frequently controversial career as major league infielder, but rather the 30 years that followed as manager, coach, scout, mentor, and teacher to young athletes across the country.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

Contract Card File. Cooperstown, N.Y.: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Player File, Norman Arthur Elberfeld. Cooperstown, N.Y.: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.]

Nemec, David. Personal E-mail Correspondence, May 19-20, 2005.

The Baseball Encyclopedia. Pete Palmer and Gary Gillete, ed. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2004.

Dewey, Donald, and Nicholas Acocella. The Black Prince of Baseball: Hal Chase and the Mythology of Baseball Wilmington, De.: Sport Classic Books, 2004.

Ervin, Edgar. Pioneer Histroy of Meigs County, Ohio to 1949, including, Masonic History of the Same Period. [Ohio] : Meigs County Pioneer Society, [1949].

Hunter, Ben, with Harlin Messer, ed. Memories of Hunter. [Minden, La.]: Coca-Cola Bottling Co. of Minden, 1997.

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball: The Official Record of Minor League Baseball, 2nd ed. Durham, N.C.: Baseball America, 1997.

Kohout, Martin Donell. Hal Chase: The Defiant Life and Turbulent Times of Baseball's Biggest Crook. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2001.

Lee, Bill. The Baseball Necrology: The Post-baseball Lives and Deaths of Over 7,600 Major League Players and Others. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2003.

Neft, David S., Richard M. Cohen, and Michael L. Neft. The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball, 24th ed. New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 2004

Nemec, David. The Great Encyclopedia of 19th-Century Major league Baseball. New York: Donald I. Fine Books, 1997.

Spatz, Lyle. Yankees Coming, Yankees Going: New York Yankee Player Transactions, 1903 Through 1999. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2000.

Spink, Alfred H. The National Game, 2nd ed. Carbondale, Ill.: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000 (reprint; originally published, 1911).

Spink, J.G. Taylor and Paul A. Rickart, comp. Daguerreotypes. St. Louis, MO : Sporting News Publishing Co., 1958.

Total Baseball: The Ultimate Baseball Encyclopedia. Toronto: Sport Classic Books, 2004.

Wright, Marshall D. The Southern Association in Baseball, 1885-1961. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2002.

Wright, Marshall D. The Texas League in Baseball, 1888-1958. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2004.

Burr, Harold. "Women in Baseball," Baseball Magazine (August 1933).

Gregorich, Barbara. "Jackie and the Juniors vs. Margaret and the Bloomers," in The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History, no. 13 (1993).

Atlanta Daily Constitution

Boston Globe

Chicago Daily Tribune

Christian Science Monitor

Cincinnati Enquirer

The Dallas Morning News

Los Angeles Times

National Police Gazette

New York Times

Sporting Life

The Sporting News

Reach Official Baseball Guide

Spalding's Official Baseball Guide

[Elberfeld, John K.] Early Elberfelds in Germany and America, Internet URL: http://www.j-elberfeld.com/KidElberfeld/Genealogy.htm, last accessed, June 16, 2005.

Family Tree Maker's Genealogy Site: John K. Elberfeld, Internet URL: http://familytreemaker.genealogy.com/users/e/l/b/John-K-Elberfeld/TREE/0..., last accessed, June 16, 2005.

This article was written by Terry Simpkins.

Kid Elberfeld, called "the dirtiest, scrappiest, most pestiferous, most rantankerous [sic], most rambunctious ball player that ever stood on spikes" for his vicious arguments on the diamond, patterned his combative style after that of his favorite team, the Baltimore Orioles of the mid-1890s. He believed, like those Oriole players, that an umpire should be kept in his place, and that what happened behind an arbiter's back was none of his business. But, when Elberfeld kept his volatile temper in check, he was also an "ideal infielder--full of ginger." Called by George Stallings one of the two best shortstops in baseball, his throwing arm was "cyclonic," and, though only 5'7," 158 lbs., he was fearless in turning the double play. Not surprisingly, he was frequently spiked, and by 1907 wore a whalebone shin guard on his right leg for protection. He was also one of the best hitting shortstops of his day, with a career .271 average, and a master at getting hit by close pitches. He perfected the art of angling his body in toward the plate, holding his arms in such as way as to take only a glancing blow while simultaneously appearing to make an honest attempt to avoid the pitch, and then, for effect, shouting and gesticulating at the pitcher. He became so adept at this that he still ranks 13th on the career hit by pitch list, with 165.

Norman Arthur Elberfeld was born on April 13, 1875, in Pomeroy, Ohio, on the Ohio River, between Cincinnati and Pittsburgh. His parents, Philip Elberfeld, a shoe merchant, and Katherine Eiselstein, were German immigrants who had settled in Meigs County, Ohio in the mid-nineteenth century. Norman was the tenth of eleven children--six boys and five girls--though the youngest child died when Kid was six years old. In 1878 the family moved to Cincinnati. Called "Kid" from his earliest days, Elberfeld had only a few years of formal schooling, and as a youngster played mainly hockey and baseball. From 1892 to 1894 he captained local baseball teams in the Norwood and Bond Hill neighborhoods of Cincinnati and played nearly every position, including catcher. In 1895, Elberfeld joined an independent team in Clarksville, Tennessee, managed and partly owned by former major leaguer Billy Earle.

Elberfeld's first professional job came the next season when he and Earle joined the Dallas Navigators of the Texas Association. A pre-season contract dispute with Montgomery was settled in Dallas' favor, but Elberfeld's season with the Navigators ended abruptly in May due to a leg injury. Jumping his contract with Dallas (possibly under the influence of Earle, who left at the same time), he recovered enough to latch on with a club in Lexington, Kentucky, where Jake Wells of the Richmond Bluebirds spotted him. Elberfeld played with Richmond of the Atlantic League in 1897. His .335 batting average and 45 stolen bases attracted the attention of the Philadelphia Phillies, who purchased his contract in September.

Elberfeld didn't play for Philadelphia in 1897, and his 1898 major league debut was delayed by knee injuries caused by a spring training bathtub fall. Finally, on May 30, he started the first game of a doubleheader against Louisville at third base and belted two doubles, got hit by a pitch, and committed two errors in the field. He quickly became a favorite with the Philadelphia fans, but poor fielding and a penchant for interfering with opposing runners left the local writers less impressed. One wrote: "Elberfeld might as well learn now that Philadelphia ballcranks will not stand for his minor league methods. What we want [are] ball players, not toughs." He played only 14 games for Philadelphia, and, though presented with a gold watch during a late-June game at Cincinnati by his hometown fans, was sold to the Western League Detroit Tigers in July, where he was ejected and fined in one of his first games. He finished the year with a lowly .238 average.

In 1899, Elberfeld hit .308 and stole 23 bases, earning him another chance in the majors. The Cincinnati Reds purchased his contract in August, but he injured his back, batted and fielded poorly, and was generally overshadowed by another rookie acquired around the same time, Sam Crawford. He jumped back to Detroit in 1900, where, as the "most aggressive" player on the "most aggressive and scrappiest" team in the newly renamed American League, he was ejected from three games during one eight-game stretch in June. Though he batted only .263, he led all shortstops with an astonishing average of over seven successful chances per game. He also married Emily Grace Catlow on October 10, and settled in Chattanooga, where he raised chickens on his farm during off seasons, and, later, tended to his apple orchard.

Elberfeld remained with Detroit for the next 2½ years. In 1901, as the Tigers staked their claim to major league status, he batted .308 with 11 triples and three home runs, all of which would remain his major league career highs. Near the end of the 1902 season, New York Giants' owner John T. Brush and manager John McGraw attempted to beef up their last place team by signing several Detroit players, and reportedly signed Elberfeld to a two-year contract for $4500 per year. McGraw's personality appealed to Elberfeld. "McGraw always liked me," Elberfeld said. "I played his aggressive style of ball. And I would have liked to have played for him." But the 1903 peace agreement returned Elberfeld to Detroit, and, when Edward Barrow was suddenly named to replace suicide-victim Win Mercer as new Detroit manager, Barrow inherited an unhappy shortstop. Though Elberfeld started fast, batting .431 after the first three weeks of the season, his hitting soon tailed off and his fielding was shoddy. On June 2, Barrow fined and suspended him for "loaferish conduct," suspecting Elberfeld of playing poorly to force a trade to the St. Louis Browns. Eight days later, Barrow did trade him, not to St. Louis, but to the New York Highlanders.

The move nearly derailed the nascent peace treaty between the leagues. Brush, opposed to peace in the first place, viewed the trade as an attempt by AL President Ban Johnson to siphon fans from the Giants. Brush badgered NL President Harry Pulliam into declaring that Johnson had violated the "spirit if not the letter" of the treaty and persuaded Pulliam to let McGraw use George Davis--then the subject of a dispute between the Giants and the Chicago White Sox--at shortstop. The case dragged on for weeks. In the meantime, Elberfeld got himself charged with disorderly conduct and fined for throwing a bottle (some reports say a knife) at a hotel waiter. Ultimately, the other NL owners decided they couldn't afford another interleague war, and on July 20 repudiated Brush's position. One of Elberfeld's career highlights came a short while later, on August 1, in a 3-2 victory Highlander victory over Philadelphia ace Rube Waddell. Elberfeld made all four New York hits and drove in all three runs as Waddell struck out 13 New Yorkers. It was after his arrival in New York, too, that sportswriter Sam Crane dubbed Elberfeld "Tabasco" Kid, referring to Elberfeld's now infamous temper and "peppery" style of play.

Over the next three years with New York, Elberfeld solidified his reputation as one of the best hitting shortstops in baseball. From 1904 to 1906, he had the highest batting (.275) and on-base-plus-slugging (.688) percentages of any shortstop in the American League, and second in the majors only to Honus Wagner. But injuries and suspensions continued to dog him; the Highlanders might have won pennants in 1904 and 1906 had Elberfeld not missed 89 games during those years. In late 1906 he also had two memorable run-ins with umpire Silk O'Loughlin. The first, on August 8, occurred when Elberfeld was denied first base by after being hit by a pitch, prompting him to menace the umpire with a bat. Then, on September 3, the two went at it again in a brawl described by the New York Times as "one of the most disgraceful scenes ever witnessed on a baseball field." The Highlanders were in a close pennant race with Chicago, and when Elberfeld was suspended for only a total of eight games by President Johnson, some viewed it as an act of favoritism toward the Highlanders.

Elberfeld's last years in New York were difficult. He feuded with teammates Wid Conroy, Jimmy Williams, Ira Thomas, and Hal Chase, and, in July 1907, was suspended by Highlander owner Frank Farrell for what the New York Times called "indifferent work in the field and at the bat." Elberfeld, harboring unrealized managerial aspirations, again sought to force a trade (this time with Washington) through sulking and lackadaisical play. When it was announced between games of a July 26 doubleheader that Conroy would replace Elberfeld, 8,000 fans greeted the news with "tumultuous" applause. After Elberfeld apologized to manager Clark Griffith, Farrell lifted the suspension on August 15 and, before 1908, Elberfeld was even offered a contract for $2700--with a $1000 bonus if he behaved himself.

On May 1, 1908, with the New Yorkers tied for first place, Elberfeld was severely spiked by Washington outfielder Bob Ganley, essentially ending Elberfeld's season. The team continued to play well without him through May, but won only seven games during June. On June 25, Farrell finally forced Griffith to resign, and Elberfeld got his chance to be manager. His tenure was a disaster. New York lost 15 of their next 18 games and the Washington Post soon quoted an unnamed Highlander saying: "We are ... playing under the direction of a crazy man. It won't take Elberfeld more than two weeks to make us the most demoralized ball team that the American League has ever known. He thinks he is a manager, but he can't convince any one but himself that he has the first qualification for the place. It's a joke." But Elberfeld himself apparently did harbor doubts about his qualifications; some years later Baseball Magazine reported that he wouldn't select the team's starting pitchers without first consulting his wife. Regardless of who picked the pitchers, the Highlanders sank to last place, Chase jumped the team in early September, and Elberfeld's sole stint as a major league manager ended with a dismal 27-71 record.

Though replaced by George Stallings as manager after the season, Elberfeld remained with the team, reluctantly, as a player in 1909; his nasty reputation, high salary, and history of injuries made him difficult to trade. His battered legs forced him to play more at third base, a familiar position from his early days and one for which he was well-suited because of his strong arm. Rusty from his long lay off, Elberfeld batted only .237 that year, but showed enough life to enable Stallings to sell him to Washington in December. The next spring, he began coaching young players from D.C.-area town and high school teams, an occupation that would dominate his activities after his playing days ended. "[Kids are] the future players, future fans, and future owners," he later said. "We need to teach them the game from the time they are old enough to swing a bat."

Elberfeld remained with Washington for two years, and manager Jimmy McAleer twice selected Elberfeld to play on post-season "all-star" teams formed to keep the pennant-winning A's sharp for their upcoming World Series appearances. In 1911, Elberfeld played through ankle, hip, and back injuries. Though he batted a solid .272 and posted a career high .405 OBP, in 1912 the new Nats manager Griffith was determined to go with younger players, and, prior to the season, Elberfeld was sold to Montgomery of the

Southern Association. He batted .260 in 78 games forthe Rebels, then moved on to the Chattanooga Lookouts in 1913 as player-manager where he batted .332 in 94 games. He was then hired to manage New Orleans, but after a change in team ownership left him jobless, Brooklyn signed him as a coach and utility player. Elberfeld played his final major league game on September 24, 1914, entering the game, ironically, as a late-inning defensive replacement when starting shortstop Dick Egan was ejected for arguing a call.

His big league days over, Elberfeld forged a second career as a minor league player and manager, primarily in the Southern Association. He spent three more years at Chattanooga, taking over as manager in July 1915. In 1918, he managed Little Rock, playing sporadically, and worked briefly at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, as a Y.M.C.A. director, teaching soldiers to throw hand grenades like baseballs. Two years later he managed Little Rock to a league championship, though they were upset by the Class B Texas League champions Fort Worth in the post-season series. He stayed with Little Rock for four more seasons, followed by stints in Mobile, Chattanooga and Little Rock again, and Springfield in the Western Association. After scouting for Little Rock and Atlanta, he finished his minor league managerial career in 1936 with the Fulton (Kentucky) Eagles in the Class D Kitty League, even appearing in one last game as a 61-year-old pinch hitter.

Though an utter failure as a leader of mature major league players, Elberfeld was highly successful working with younger athletes. He discovered or helped develop many major league players, including Casey Stengel, Travis Jackson, Bill Terry, Cecil Travis, and Jim Turner, though his influence wasn't uniformly positive--Burleigh Grimes blamed his own notoriously bad temper on his early exposure to Elberfeld. Beginning in the 1920s, he ran or participated in baseball schools throughout the South, even managing the female pitcher Jackie Mitchell on his 1931 barnstorming team, the Lookout Juniors. He had a lot of experience tutoring female athletes; of his six children, five were girls, and during the mid-1920s they competed as boxers, held state and national amateur championships in tennis and swimming, and even formed a basketball team around Chattanooga called the "Elberfeld Sisters."

In the early 1940s, Elberfeld ran annual baseball camps sponsored by Coca-Cola in Minden, Louisiana. He would regale the boys with reminiscences of his career and show off the scars crisscrossing his legs. Though patient with his more uncoordinated charges, traces of the "Tabasco Kid" of old still remained: he called them "rock" or "hardhead" when they botched a play, and passed along tips on the finer points of bench jockeying.

Early in 1944, Elberfeld caught a cold and, on January 13, died of pneumonia at Erlanger Hospital in Chattanooga. He was buried in Chattanooga Memorial Park. Three years later, on July 6, 1947, Elberfeld's grandson unveiled a plaque at Engel Stadium in Chattanooga. Without a trace of irony, it read, "In memoriam, Norman Elberfeld ... a sportsman and a friend ... dedicated 1947 by his many friends in baseball," honoring not his frequently controversial career as major league infielder, but rather the 30 years that followed as manager, coach, scout, mentor, and teacher to young athletes across the country.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

Contract Card File. Cooperstown, N.Y.: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Player File, Norman Arthur Elberfeld. Cooperstown, N.Y.: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.]

Nemec, David. Personal E-mail Correspondence, May 19-20, 2005.

The Baseball Encyclopedia. Pete Palmer and Gary Gillete, ed. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2004.

Dewey, Donald, and Nicholas Acocella. The Black Prince of Baseball: Hal Chase and the Mythology of Baseball Wilmington, De.: Sport Classic Books, 2004.

Ervin, Edgar. Pioneer Histroy of Meigs County, Ohio to 1949, including, Masonic History of the Same Period. [Ohio] : Meigs County Pioneer Society, [1949].

Hunter, Ben, with Harlin Messer, ed. Memories of Hunter. [Minden, La.]: Coca-Cola Bottling Co. of Minden, 1997.

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball: The Official Record of Minor League Baseball, 2nd ed. Durham, N.C.: Baseball America, 1997.

Kohout, Martin Donell. Hal Chase: The Defiant Life and Turbulent Times of Baseball's Biggest Crook. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2001.

Lee, Bill. The Baseball Necrology: The Post-baseball Lives and Deaths of Over 7,600 Major League Players and Others. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2003.

Neft, David S., Richard M. Cohen, and Michael L. Neft. The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball, 24th ed. New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 2004

Nemec, David. The Great Encyclopedia of 19th-Century Major league Baseball. New York: Donald I. Fine Books, 1997.

Spatz, Lyle. Yankees Coming, Yankees Going: New York Yankee Player Transactions, 1903 Through 1999. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2000.

Spink, Alfred H. The National Game, 2nd ed. Carbondale, Ill.: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000 (reprint; originally published, 1911).

Spink, J.G. Taylor and Paul A. Rickart, comp. Daguerreotypes. St. Louis, MO : Sporting News Publishing Co., 1958.

Total Baseball: The Ultimate Baseball Encyclopedia. Toronto: Sport Classic Books, 2004.

Wright, Marshall D. The Southern Association in Baseball, 1885-1961. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2002.

Wright, Marshall D. The Texas League in Baseball, 1888-1958. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2004.

Burr, Harold. "Women in Baseball," Baseball Magazine (August 1933).

Gregorich, Barbara. "Jackie and the Juniors vs. Margaret and the Bloomers," in The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History, no. 13 (1993).

Atlanta Daily Constitution

Boston Globe

Chicago Daily Tribune

Christian Science Monitor

Cincinnati Enquirer

The Dallas Morning News

Los Angeles Times

National Police Gazette

New York Times

Sporting Life

The Sporting News

Reach Official Baseball Guide

Spalding's Official Baseball Guide

[Elberfeld, John K.] Early Elberfelds in Germany and America, Internet URL: http://www.j-elberfeld.com/KidElberfeld/Genealogy.htm, last accessed, June 16, 2005.

Family Tree Maker's Genealogy Site: John K. Elberfeld, Internet URL: http://familytreemaker.genealogy.com/users/e/l/b/John-K-Elberfeld/TREE/0..., last accessed, June 16, 2005.