'''Terrible Terry''' By Bill Terry, Manager of the New York Giants, as told to Arthur Mann

The Saturday Evening Post, January 29, 1938, Number 51

HAVE you ever hocked your wife's engagement ring? Even though the ring may have cost only forty-five dollars, as Mrs. Terry's did, pawning it still carries a shame and self-reproach that no amount of later success can erase from your memory. You see, I had bought that little ring with savings from meager baseball salaries and, when I married her, I made glowing promises that only an eighteen-year-old groom can fashion. Being very young, too, she believed my promises of gold and glory in baseball, and believed them with a sublime faith that amazed even me. Well, there we were, in a cafeteria at Shreveport, Louisiana, with our last cent invested in a much-needed breakfast. I had two weeks in which to justify my demand for a pay rise from $140 to $155 a month, plus ten dollars for my wife's expenses from New Orleans, where we had wintered after our honey-moon. Since the ball club would foot my training-and glory in camp expenses, the question of moment concerned how my bride would eat. The engagement ring was the answer. Taking that forty-five-dollar ring from her finger was a confession of desperation, a last straw. It was an unspoken promise that she would not be obliged to make further sacrifices for my baseball career. And so it was pledged for fifteen dollars - two weeks of food. We lived in a small room at a low-rate hotel. The carpet was worn threadbare. Cracked and yellow shades hung at the window. Our wardrobe was a corner of the room curtained off with an old portiere. After two weeks of hard work and anxious waiting, the regular season started. I re deemed the ring with part of my first pay check and went on to a fair season in the Texas of the Southern Association, early the next year, was strong indication that few held high respect for my pitching. It wasn't failure, but it wasn't progress. I refused to risk a repetition of the Shreveport nightmare, and so ended my baseball career. I refused to report to Little Rock. I remained in Memphis and hunted for any kind of a steady job, which was a job in itself, because it was April of 1918, and the nation was at war.

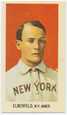

Engagement-Ring Insurance

TODAY I am referred to occasionally in the newspapers and magazines as "What'sin-it-for-me Terry." I am pictured as a penny-pinching, nickel-nursing, dime-digging Croesus who has one eye on the standing of the National League' clubs and the other on my bank balance, but the reason for that state of mind is never given. Therefore, I feel obliged to explain that whatever lust for gold - silver will do in a pinch-I may have, can be traced back to that Shreveport horror. It is self-explanatory. I simply don't want to be again in a predicament that will force me to hock my wife's engagement ring. If that makes me a criminal, then I say here's to crime! This biographical treatise is in no sense an Areopagitica, to use an old baseball term, for there is nothing to be defended. It always seemed to me that both sides of a situation contain news, and, if all the talk about Terrible Terry carries interest, surely Terry's unspoken and unpublished views might contain a readable paragraph or two. I have never been particularly moved by any of the pro or con written about me, especially the con. Once in a while an ornery paragraph gets under my skin, but the next day's ball game crowds out the irritation. Besides, technical and financial success has given most of the critical heckling a boomerang twist, as the following chain of incidents will indicate. I developed an even greater respect for money after refusing to report to Little Rock in the spring of 1918. The steady job I finally landed paid $18.50 a week for making storage batteries. But it was eighteen-fifty more than nothing at all, and there was plenty of room for advancement. Because it was impossible to get along on that salary, I was constantly in a financial hole and seeking to climb out by the simple process of working like a truck horse. I learned everything there was to be learned in that shop about building a storage battery. The investment paid dividends some months later when the company began to give cash bonuses for heavy output of work. Young Terry came as close to mass production as one man can, and eventually I collected enough extra dough to keep my head above water. I might have been building storage batteries to this day if the owner's son hadn't tried to tell me how to run my work and division. After my long night-and-day toil, I felt that there wasn't much he could tell me about that shop, especially coming from a front office. I quit. I took a job with an oil company and I've worked with them for nineteen years. The oil company had baseball teams, and it took them no time to ferret me out for the sole purpose of helping the cause on Saturdays and Sundays. In the summer of 1921 I took a two-weeks vacation and cleared $600 playing semipro ball with my own team. That was when Kid Elberfeld, manager of the Little Rock club, to which I had refused to report, decided that I was worth following up. And so he got in touch with John J. McGraw, who bought me, sight unseen, for $750. The Inside Story of a Holdout Now, reporting to the Giants was considerably better than going to Little Rock as a castoff. McGraw had struck the pennant mother lode again, and there was no telling how far I might go from this springboard. The water was deep and, as in the case of the storage-battery job, there was plenty of room for advancement. And so I tackled league baseball again.

HAVE you ever hocked your wife's engagement ring? Even though the ring may have cost only forty-five dollars, as Mrs. Terry's did, pawning it still carries a shame and self-reproach that no amount of later success can erase from your memory. You see, I had bought that little ring with savings from meager baseball salaries and, when I married her, I made glowing promises that only an eighteen-year-old groom can fashion. Being very young, too, she believed my promises of gold and glory in baseball, and believed them with a sublime faith that amazed even me. Well, there we were, in a cafeteria at Shreveport, Louisiana, with our last cent invested in a much-needed breakfast. I had two weeks in which to justify my demand for a pay rise from $140 to $155 a month, plus ten dollars for my wife's expenses from New Orleans, where we had wintered after our honey-moon. Since the ball club would foot my training-and glory in camp expenses, the question of moment concerned how my bride would eat. The engagement ring was the answer. Taking that forty-five-dollar ring from her finger was a confession of desperation, a last straw. It was an unspoken promise that she would not be obliged to make further sacrifices for my baseball career. And so it was pledged for fifteen dollars - two weeks of food. We lived in a small room at a low-rate hotel. The carpet was worn threadbare. Cracked and yellow shades hung at the window. Our wardrobe was a corner of the room curtained off with an old portiere. After two weeks of hard work and anxious waiting, the regular season started. I re deemed the ring with part of my first pay check and went on to a fair season in the Texas of the Southern Association, early the next year, was strong indication that few held high respect for my pitching. It wasn't failure, but it wasn't progress. I refused to risk a repetition of the Shreveport nightmare, and so ended my baseball career. I refused to report to Little Rock. I remained in Memphis and hunted for any kind of a steady job, which was a job in itself, because it was April of 1918, and the nation was at war.

Engagement-Ring Insurance

TODAY I am referred to occasionally in the newspapers and magazines as "What'sin-it-for-me Terry." I am pictured as a penny-pinching, nickel-nursing, dime-digging Croesus who has one eye on the standing of the National League' clubs and the other on my bank balance, but the reason for that state of mind is never given. Therefore, I feel obliged to explain that whatever lust for gold - silver will do in a pinch-I may have, can be traced back to that Shreveport horror. It is self-explanatory. I simply don't want to be again in a predicament that will force me to hock my wife's engagement ring. If that makes me a criminal, then I say here's to crime! This biographical treatise is in no sense an Areopagitica, to use an old baseball term, for there is nothing to be defended. It always seemed to me that both sides of a situation contain news, and, if all the talk about Terrible Terry carries interest, surely Terry's unspoken and unpublished views might contain a readable paragraph or two. I have never been particularly moved by any of the pro or con written about me, especially the con. Once in a while an ornery paragraph gets under my skin, but the next day's ball game crowds out the irritation. Besides, technical and financial success has given most of the critical heckling a boomerang twist, as the following chain of incidents will indicate. I developed an even greater respect for money after refusing to report to Little Rock in the spring of 1918. The steady job I finally landed paid $18.50 a week for making storage batteries. But it was eighteen-fifty more than nothing at all, and there was plenty of room for advancement. Because it was impossible to get along on that salary, I was constantly in a financial hole and seeking to climb out by the simple process of working like a truck horse. I learned everything there was to be learned in that shop about building a storage battery. The investment paid dividends some months later when the company began to give cash bonuses for heavy output of work. Young Terry came as close to mass production as one man can, and eventually I collected enough extra dough to keep my head above water. I might have been building storage batteries to this day if the owner's son hadn't tried to tell me how to run my work and division. After my long night-and-day toil, I felt that there wasn't much he could tell me about that shop, especially coming from a front office. I quit. I took a job with an oil company and I've worked with them for nineteen years. The oil company had baseball teams, and it took them no time to ferret me out for the sole purpose of helping the cause on Saturdays and Sundays. In the summer of 1921 I took a two-weeks vacation and cleared $600 playing semipro ball with my own team. That was when Kid Elberfeld, manager of the Little Rock club, to which I had refused to report, decided that I was worth following up. And so he got in touch with John J. McGraw, who bought me, sight unseen, for $750. The Inside Story of a Holdout Now, reporting to the Giants was considerably better than going to Little Rock as a castoff. McGraw had struck the pennant mother lode again, and there was no telling how far I might go from this springboard. The water was deep and, as in the case of the storage-battery job, there was plenty of room for advancement. And so I tackled league baseball again.