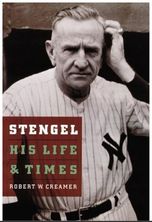

Stengel: His Life and Times by Robert W. Creamer

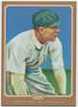

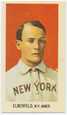

The following autumn, Casey Stengel reported to the Montgomery team at its training camp in Pensacola, Florida. His manager was a former major-league outfielder named Johnny Dobbs, but Stengel paid more attention to an old shortstop named Norman Elberfeld, known in baseball as the Tabasco Kid, or, more commonly, just Kid Elberfeld was even older than Dobbs; he had spent thirteen seasons in the majors and had managed the New York Highlanders (later to be called the Yankees) for part of a season. He was a smallish man, about five feet seven, peppery and pugnacious. There was a fierce rivalry between Montgomery, managed by Dobbs, and Atlanta, man-aged by a fellow named Dolan, and feud-minded Southerners referred to games between the clubs as battles between the McDobbs Clan and the McDolans. In Atlanta, the Montgomery players rode from their hotel to the ball park in an open horse-drawn stage. When Atlanta fans saw them passing they would jeer and hoot, and occasionally some would run close to the wagon as though to spit or let loose a particularly cutting epithet.

Elberfeld would sit on the side step of the wagon holding a bat in his hands, and whenever people came too close he'd threaten to whack them with the bat. Elberfeld took a liking to Stengel and told the twenty-one-year-old outfielder, "Listen, if you want to get to the big leagues, watch me." He taught Stengel the niceties of the hit-and-run, showed him how to bat a ball behind the runner and how to coordinate his efforts at bat with a base runner so that he could poke a ground ball through the spot vacated by an infielder moving over to cover the base the runner was heading for. Elberfeld showed Stengel how to stand close to the plate at bat so that he could get himself hit with a pitched ball when it was especially desirable to get to first base, and how to defray suspicion that you'd gotten yourself hit on purpose by throwing your bat angrily toward the mound and moving threateningly toward the pitcher, shouting and cursing.

Stengel was an apt student, but sometimes he didn't learn as well as Elberfeld wanted him to. The old shortstop liked to work a play when he was at bat and the swift-running Stengel was on second base. He'd have Stengel break toward third base on the pitch, which would prompt the shortstop to move toward second base and the third base-man toward third, each anticipating a throw and a possible rundown with the rash young base runner caught between bases. Elberfeld, who had great bat control, would poke a simple ground ball to the left side, and neither the third baseman nor the shortstop could get back into position in time to field it, which meant that Stengel would reach third easily and sometimes be able to keep going all the way to home plate. Now and then the play would backfire. Elberfeld wouldn't be able to hit a grounder and instead would hit a pop fly or a soft line drive. He had cautioned his pupil to be alert to such a possibility, but Stengel, vain about his base running, his eyes set on reaching third, would run blindly and be easily doubled off second. This happened a couple of times, to Elberfeld's considerable annoyance. When it happened a third time-Stengel running full tilt toward third while an infielder was settling under an Elberfeld pop-up-the Tabasco Kid raced down the third-base line, waving his bat and screaming. The startled young Stengel put on the brakes, wheeled, and sprinted back toward second base, too late to avoid being doubled off, but away from the cursing Elberfeld anyway.

When he was still in spring training with Montgomery, Stengel one day noticed a metal cover half hidden in the lush grass of the outfield. Always curious, he opened the cover and found that it concealed a shallow hole containing water pipes and valves and enough space to hide a crouching man. Glancing around and realizing no one was watching, he ducked into the hole and closed the lid, holding it open just wide enough so that he could keep an eye on what was going on elsewhere around the field. Someone hit a high lazy fly ball in his direction, and when everyone looked toward the outfield Stengel got his desired effect: No one could imagine where he had gone. Then he climbed out of his hiding place, holding the metal cover over his head. He planned to hold the cover like a shield and let the ball bounce off it before he caught it, but it was too heavy to maneuver easily and at the last moment he had to drop it and grab the ball one-handed.

A scout for the Washington Senators named Mike Kahoe heard about that and when he was asked his opinion of Stengel as a major-league prospect said, "Well, he handles the bat well, and he can run and field and throw. He's a dandy ballplayer, but it's all from the neck down." His reputation for eccentricity was growing. A lot of people enjoyed his fooling, but not everyone. "Being a clown wasn't safe in the minors," Stengel said. "Some of them bush-league managers could hit you with a bat at fifty feet." But he batted .290 with Montgomery and led all outfielders in the league in assists. He had developed in three seasons from a raw, un-schooled greenhorn into a skilled, competent professional. Brooklyn was well aware of his progress, and in August, a month before the end of the Southern Association season, it announced that it would exercise its option and reclaim Stengel's contract. He was ordered to report to the Brooklyn club as soon as the Southern Association season ended in mid-September. Montgomery's last game was on Sunday, September 15.

Elberfeld took charge of Stengel's departure. He made him buy a new suit. Stengel protested, saying that he was saving his money for dental school. Elberfeld said, "You're going to the big leagues. You're not gonna be a dentist." He told Stengel he had to dress right if he were going to be a big-leaguer, and Stengel reluctantly bought a new suit. Then Elberfeld told him he had to get rid of the cardboard suitcase he'd been using and buy a decent leather one. Stengel protested again, but Elberfeld said, "If you get caught in a hard rain with that cardboard suitcase all that you'll have left will be the handle." Stengel thought the old suitcase would see him through the few weeks of the season still remaining. Elberfeld said no, and made Stengel buy a new bag. Elberfeld also set up a farewell dinner for the departing hero and made Stengel buy the wine for it. Stengel, pinching his $150-a-month salary, disliked spending all that money, but Elberfeld's insistence that he do things right made him understand the meaning of "big league." Casey went first-class the rest of his life, and he insisted that his players understand the reasoning: "If you're a big-leaguer, act like a big--leaguer." That also meant you should be treated as a big-leaguer.

In 1953, Red Barber, long the broadcaster of Brooklyn Dodger games, refused to do the telecast of the World Series between the Dodgers and the Yankees that year unless the sponsor would let him negotiate for better payment than the $200 a game he had been paid a year earlier. The sponsor told him he could take it or leave it. When Walter O'Malley, the Dodger owner, failed to support Barber in the dispute, Barber left both the World Series broadcast and the Dodgers. He moved to the Yankees the next season, but during that 1953 Series he was without a job. After the Yankees won the final game of the Series, Barber made his way through the crowd in the dressing room to congratulate Stengel. Casey was surrounded by reporters in the usual mob scene when Barber put out his hand and said, "Congratulations, Casey." Stengel raised his eye-brows, grabbed Barber's hand and said, "Let me congratulate you! I want to tell you, a major-league job is worth major-league money!" The Tabasco Kid sent his protege to the big leagues in style, a style he'd never forget

. ----

'''Stengel: His Life and Times by Robert W. Creamer''' One of the most endearing of American heroes, Casey Stengel guided the New York Yankees to ten pennants in twelve seasons. Here is the brilliant manager stripped naked—the person underneath all the clowning, mugging, and double-talking. Robert Creamer shows us Casey at twenty-two, famous from his very first day in the big leagues. We see Casey’s playing career fall apart as he is traded, shunted to last-place teams, hampered by injuries, considered finished—until he bats a glorious home run in the 1923 World Series. Here are Casey’s managing successes and failures—dismissed by the Yankees, he returns to the limelight with his new and inept New York Mets, the team he single-handedly lifts into the nation’s consciousness. “I’m a man that’s been up and down,” Casey said in a serious moment. Certainly his knack for bouncing back made him a legend in our national pastime. Here are the stories and gags, the Stengelian style, the full dimensions of the man.

Product Details

Paperback: 349 pages

Publisher: University of Nebraska Press; Reprint edition (March 1, 1996)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0803263678

ISBN-13: 978-0803263673

Product Dimensions: 9 x 6 x 0.8 inches

Shipping Weight: 1.2 pounds (View shipping rates and policies)

Average Customer Review: 4.4 out of 5 stars

Amazon Best Sellers Rank: #555,167 in Books

Elberfeld would sit on the side step of the wagon holding a bat in his hands, and whenever people came too close he'd threaten to whack them with the bat. Elberfeld took a liking to Stengel and told the twenty-one-year-old outfielder, "Listen, if you want to get to the big leagues, watch me." He taught Stengel the niceties of the hit-and-run, showed him how to bat a ball behind the runner and how to coordinate his efforts at bat with a base runner so that he could poke a ground ball through the spot vacated by an infielder moving over to cover the base the runner was heading for. Elberfeld showed Stengel how to stand close to the plate at bat so that he could get himself hit with a pitched ball when it was especially desirable to get to first base, and how to defray suspicion that you'd gotten yourself hit on purpose by throwing your bat angrily toward the mound and moving threateningly toward the pitcher, shouting and cursing.

Stengel was an apt student, but sometimes he didn't learn as well as Elberfeld wanted him to. The old shortstop liked to work a play when he was at bat and the swift-running Stengel was on second base. He'd have Stengel break toward third base on the pitch, which would prompt the shortstop to move toward second base and the third base-man toward third, each anticipating a throw and a possible rundown with the rash young base runner caught between bases. Elberfeld, who had great bat control, would poke a simple ground ball to the left side, and neither the third baseman nor the shortstop could get back into position in time to field it, which meant that Stengel would reach third easily and sometimes be able to keep going all the way to home plate. Now and then the play would backfire. Elberfeld wouldn't be able to hit a grounder and instead would hit a pop fly or a soft line drive. He had cautioned his pupil to be alert to such a possibility, but Stengel, vain about his base running, his eyes set on reaching third, would run blindly and be easily doubled off second. This happened a couple of times, to Elberfeld's considerable annoyance. When it happened a third time-Stengel running full tilt toward third while an infielder was settling under an Elberfeld pop-up-the Tabasco Kid raced down the third-base line, waving his bat and screaming. The startled young Stengel put on the brakes, wheeled, and sprinted back toward second base, too late to avoid being doubled off, but away from the cursing Elberfeld anyway.

When he was still in spring training with Montgomery, Stengel one day noticed a metal cover half hidden in the lush grass of the outfield. Always curious, he opened the cover and found that it concealed a shallow hole containing water pipes and valves and enough space to hide a crouching man. Glancing around and realizing no one was watching, he ducked into the hole and closed the lid, holding it open just wide enough so that he could keep an eye on what was going on elsewhere around the field. Someone hit a high lazy fly ball in his direction, and when everyone looked toward the outfield Stengel got his desired effect: No one could imagine where he had gone. Then he climbed out of his hiding place, holding the metal cover over his head. He planned to hold the cover like a shield and let the ball bounce off it before he caught it, but it was too heavy to maneuver easily and at the last moment he had to drop it and grab the ball one-handed.

A scout for the Washington Senators named Mike Kahoe heard about that and when he was asked his opinion of Stengel as a major-league prospect said, "Well, he handles the bat well, and he can run and field and throw. He's a dandy ballplayer, but it's all from the neck down." His reputation for eccentricity was growing. A lot of people enjoyed his fooling, but not everyone. "Being a clown wasn't safe in the minors," Stengel said. "Some of them bush-league managers could hit you with a bat at fifty feet." But he batted .290 with Montgomery and led all outfielders in the league in assists. He had developed in three seasons from a raw, un-schooled greenhorn into a skilled, competent professional. Brooklyn was well aware of his progress, and in August, a month before the end of the Southern Association season, it announced that it would exercise its option and reclaim Stengel's contract. He was ordered to report to the Brooklyn club as soon as the Southern Association season ended in mid-September. Montgomery's last game was on Sunday, September 15.

Elberfeld took charge of Stengel's departure. He made him buy a new suit. Stengel protested, saying that he was saving his money for dental school. Elberfeld said, "You're going to the big leagues. You're not gonna be a dentist." He told Stengel he had to dress right if he were going to be a big-leaguer, and Stengel reluctantly bought a new suit. Then Elberfeld told him he had to get rid of the cardboard suitcase he'd been using and buy a decent leather one. Stengel protested again, but Elberfeld said, "If you get caught in a hard rain with that cardboard suitcase all that you'll have left will be the handle." Stengel thought the old suitcase would see him through the few weeks of the season still remaining. Elberfeld said no, and made Stengel buy a new bag. Elberfeld also set up a farewell dinner for the departing hero and made Stengel buy the wine for it. Stengel, pinching his $150-a-month salary, disliked spending all that money, but Elberfeld's insistence that he do things right made him understand the meaning of "big league." Casey went first-class the rest of his life, and he insisted that his players understand the reasoning: "If you're a big-leaguer, act like a big--leaguer." That also meant you should be treated as a big-leaguer.

In 1953, Red Barber, long the broadcaster of Brooklyn Dodger games, refused to do the telecast of the World Series between the Dodgers and the Yankees that year unless the sponsor would let him negotiate for better payment than the $200 a game he had been paid a year earlier. The sponsor told him he could take it or leave it. When Walter O'Malley, the Dodger owner, failed to support Barber in the dispute, Barber left both the World Series broadcast and the Dodgers. He moved to the Yankees the next season, but during that 1953 Series he was without a job. After the Yankees won the final game of the Series, Barber made his way through the crowd in the dressing room to congratulate Stengel. Casey was surrounded by reporters in the usual mob scene when Barber put out his hand and said, "Congratulations, Casey." Stengel raised his eye-brows, grabbed Barber's hand and said, "Let me congratulate you! I want to tell you, a major-league job is worth major-league money!" The Tabasco Kid sent his protege to the big leagues in style, a style he'd never forget

. ----

'''Stengel: His Life and Times by Robert W. Creamer''' One of the most endearing of American heroes, Casey Stengel guided the New York Yankees to ten pennants in twelve seasons. Here is the brilliant manager stripped naked—the person underneath all the clowning, mugging, and double-talking. Robert Creamer shows us Casey at twenty-two, famous from his very first day in the big leagues. We see Casey’s playing career fall apart as he is traded, shunted to last-place teams, hampered by injuries, considered finished—until he bats a glorious home run in the 1923 World Series. Here are Casey’s managing successes and failures—dismissed by the Yankees, he returns to the limelight with his new and inept New York Mets, the team he single-handedly lifts into the nation’s consciousness. “I’m a man that’s been up and down,” Casey said in a serious moment. Certainly his knack for bouncing back made him a legend in our national pastime. Here are the stories and gags, the Stengelian style, the full dimensions of the man.

Product Details

Paperback: 349 pages

Publisher: University of Nebraska Press; Reprint edition (March 1, 1996)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0803263678

ISBN-13: 978-0803263673

Product Dimensions: 9 x 6 x 0.8 inches

Shipping Weight: 1.2 pounds (View shipping rates and policies)

Average Customer Review: 4.4 out of 5 stars

Amazon Best Sellers Rank: #555,167 in Books