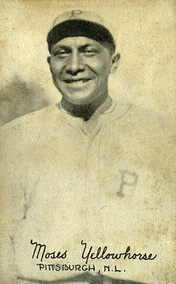

Mose J. YellowHorse

Chief Yellow HorseThis article was written by Ralph Berger.

People love stereotypes. One can force a group into a category without thinking about the individuals who make it up. After all, thought takes energy, and creators of stereotypes just might find out truths about people that they were blind to. What is worse, they might have to change their minds. The downside to such a high-minded dismissal of stereotypes, of course, is that they often contain an element of truth. Unfortunately, Mose J. YellowHorse for much of his life contributed to the stereotype of the drunken Native American.

Nevertheless, YellowHorse redeemed his dignity by living a life of atonement to himself and to his people. Since he played just two years in the major leagues, his redemption was not so much one of athleticism as of the soul. He stopped his drinking cold turkey and got a steady job. His people, once alienated from him, accepted him back and he became an elder in the Pawnee tribe. The tribe was always proud of him for his athletic achievements, but now they respected him for his beating drink and gaining steady employment. As an elder of the tribe, YellowHorse lent the wisdom and knowledge he gained from his trials to those who sought him out.

The Trail of Tears has never really ended. Native Americans were rounded up onto reservations much like concentration camps and denied their inalienable rights to the land they once roamed. Some shrugged it off as Manifest Destiny; others condemned it as outright robbery. Either way, eons of freedom came to an end for the Indians. They became strangers in their own land.

The Pawnees, rich in religion and mysticism and whose history went back many centuries, were herded into camps in the Oklahoma Territory. The tribe was divided into four bands: Skidi (Wolf Band), Kilkihaki (Little Earth Lodge Band), Tsawi (Asking for Meat Band), and Petahauirata (Man Going Downstream Band).

Clara and Thomas YellowHorse were children when the Pawnees were forced to relocate from Nebraska to Oklahoma in 1875. Though not as long a journey as the Trail of Tears, it was just as arduous, with many dying of disease and starvation. In 1879 the population of the Pawnees was reported at 1,440, a drop of fifty percent in 15 years. Thomas and Clara met in Oklahoma Territory, married (just when is not known), and settled down on a farm.

It was in Pawnee, Oklahoma Territory, that Mose J. YellowHorse was born on January 28, 1898. (Todd Fuller shows that the unusual spellings are correct in Sixty Feet 6 Inches.) The family belonged to the Skidi or Wolf Band of Pawnees. YellowHorse is considered by many to have been the first full-blooded American Indian to have played in the major leagues. Other Native Americans who played major league baseball such as Charles Albert (Chief) Bender, John (Chief) Meyers, and Lou Sockalexis were not believed to have been full-blooded natives.

Mose developed his pitching arm by throwing stones at small game to help feed the family. Powerfully built at 5'10" and 180 pounds but an amiable person, he was quick to make friends and had a great sense of humor.

Still, when he reported to Pittsburgh in 1921, he was both exhilarated and anxious as to how to conduct himself in a big industrial city with large steel plants and towering smokestacks, not to mention masses of humanity. Needing someone to help him adapt to the big city, he gravitated toward shortstop Rabbit Maranville, a notorious hellraiser, to say the least. The two became friends, rooming together on the road. They caroused and drank so much that Bill McKechnie, manager of the Pirates at that time, also roomed with them to keep an eye on the two crazies. One night McKechnie went out to catch a movie. Maranville and YellowHorse after some libation decided to catch pigeons as they sailed past their sixteenth-story window in the hotel. After nabbing their lot, they stuffed some of them into McKechnie's closet and the rest in YellowHorse's closet. When McKechnie returned from his movie, he found YellowHorse and Maranville sound asleep and thought himself a lucky man. Then he opened his closet and let out a howl as a flock of pigeons swarmed at him. Maranville awoke at this point and told McKechnie not to open YellowHorse's closet because his pigeons were in there. McKechnie understandably decided not to room with them anymore.

Because of his easygoing manner and sense of humor, YellowHorse got along somewhat more easily in the white man's world than most other Native Americans. The roles were reversed, however, when he took the mound. He was no longer the oppressed Indian; he was the guy with the hard round sphere that would be hurled at a white batter. On September 26, 1922, for example, YellowHorse was facing Ty Cobb in an exhibition game. Cobb as usual was crowding the plate and according to witnesses was hurling racist remarks at YellowHorse, who shook off four pitches and then sent a fastball that hit Cobb between the eyes. The Tiger bench rushed the mound, but YellowHorses's teammates ran out to protect him. Was the pitch intentionally sent at Cobb's head, or did it just get away?

The Pawnees appeared to have been assimilated more easily into the mainstream of Euro-American life than did other tribes. YellowHorse and his parents wore white men's clothes and lived in a permanent structure on their own farm. He attended school as ordered by the Indian Agency, an order intended to acculturate him into American society. With this background he fit more easily into the broader society. Despite this acculturation, there must have existed a pull to retain at least some ancient customs. For a millenium the Pawnees had a rich history, and they did not give it up easily. Indeed, YellowHorse was quite knowledgeable about his tribe's culture and augmented his knowledge all of his life.

YellowHorse started playing baseball at the Chilocco Indian School in Oklahoma. He went 17-0 in 1917 for the school. He then started his professional pitching career for the Arkansas Travelers of the Southern Association. Helping the team to its first championship in 1920, he went 21-7. Kid Elberfeld, his manager at Arkansas, had batted against Walter Johnson and felt that Mose was as fast as Johnson.

In 1921 YellowHorse came into the major leagues with the Pittsburgh Pirates, making his debut on April 15 in relief of Earl Hamilton in a 3-1 win over Eppa Rixey and the Cincinnati Reds. He made a few starts but was used mainly as a relief pitcher. Spending only two years with Pittsburgh, he had an 8-4 record and then hurt his arm in 1922.

YellowHorse's tenure with the Pirates was a time of great expectations for that did not pan out. Injuries and a drinking and carousing problem also inhibited his effectiveness. Still, he was a favorite with the fans, who would often chant, "Put in YellowHorse!" when the starting pitcher began to falter. Even after he was gone the chant could still be heard. In a game against the Cardinals on July 5, 1921, YellowHorse suffered a rupture in his arm that required surgery. This put him on the injured list for two months. Hurting his arm again in 1922 (possibly from a drunken fall) began his tailspin.

Aside from his drilling Cobb between the eyes in an exhibition game, there is nothing notable about his big league career other than that he lived the high life, eventually ruining his baseball career and making his life a living hell.

YellowHorse continued to live high-and drink. He loved being the roommate of Rabbitt Maranville, who had introduced him to the liquor that would become his personal demon. Maranville would eventually end his personal struggle with alcohol, but too late to help YellowHorse.

Sent to Sacramento in 1923, YellowHorse approached several major league clubs, but found no takers. His carousing and drinking problems were noted, and the big league teams passed on him. Back in Pawnee, his tribal members were unhappy about his drinking and he became alienated from them. His drinking was destroying his baseball career and his personal life. He had effectively ended his major league career by sustaining an injury to his arm, possibly as a result of his drinking. Now he was faced with not only losing his baseball career but also his personal dignity.

In 1924 YellowHorse suffered another serious arm injury. Sacramento traded him to Fort Worth; Fort Worth sent him back to Sacramento. In January of 1926, Sacramento sold Mose to Omaha, where he pitched in his final game on May 1. That was it for his baseball career.

YellowHorse's life was in free-fall when he returned to Pawnee. Drinking heavily and drifting from odd job to odd job, he was a lost soul. From 1927 to 1945 YellowHorse earned just enough to eat and drink. He was lost in his own tribe. His tribal brothers avoided him and talked about him in whispers. Suddenly in 1945 he quit drinking, apparently without any help. Mose YellowHorse's redemption took the form of retrieval. He retrieved his dignity by stopping drinking and finding himself gainfully employed in steady work. He retrieved his status with his tribe and became an honored member.

His life changed dramatically when he stopped drinking. He was now able to keep a steady job and in time became a tribal elder. He found steady work, first with the Ponca City farm team and then with the Oklahoma State Highway Department.

Chester Gould, also born on the Pawnee reservation, used YellowHorse in his Dick Tracy comic strip as the model for a character named YellowPony. YellowPony's face bore no resemblance to YellowHorse's. Nor did his speech, which was "ugh-me-know-you"-guttural English. YellowHorse actually spoke excellent English from his days in the agency school. The only real similarity between live model and comic strip character was a big, strong physique. Most likely, Gould knowingly perpetuated the stereotypical characteristics of the Indian in presenting YellowPony to help sell his comic strip. Sadly, the general public perceived the Indian as an uneducated if noble savage. In addition, the press also represented Indian ballplayers with an overwhelming physicality.

From 1945 until his death, YellowHorse lived a clean and respectable life. He became a groundskeeper for the Ponca City ballclub in 1947 and coached an all-Indian baseball team of youngsters who were all full-blooded. He hunted and fished and made decisions as an elder of the tribe.

Mose YellowHorse died on April 10, 1964. He was 66 years old. His headstone in the Northern Indian Cemetery in Pawnee curiously shows only the years of his birth and death but no dates. His gravesite is tucked away in a far corner of the Indian part of the cemetery separated from the white section by a long row of cedar trees. YellowHorse never married and had no children. The residents of Pawnee saw to it that he had a proper burial and headstone.

Though YellowHorse was not a household name, his life in and out of baseball raises many questions and opens many wounds about the relationship between Euro-Americans and Native Americans, now strangers in their own land and forced to assimilate themselves without benefits. For example, when Euro-Americans were celebrating the prosperity of the 1920s, Native Americans still on the reservations did not participate in the fruits of that prosperity. In effect they were not permitted to participate by the very absence of laws concerning them. Unlike the black people of that time who were restricted by many Jim Crow laws and knew where they stood, the Indians had no idea where they stood in the broader society. That they went to agency schools and learned Euro-American history and English meant nothing if they could not use their knowledge to participate in society as a whole. When some people pointed out that the Native American was a vanishing race, it was not solely because they did not exist; it was also their unfortunate lot to be ignored.

YellowHorse redeemed himself after a long bout with alcoholism and became a proud member of the Pawnee tribe. His life could have gone on with continuing alcoholism until it killed him. But instead he alone took his life into his own hands and redeemed himself. Deciding he was going in a direction that would only lead to self-destruction, YellowHorse made an abrupt but healthy u-turn. He rose above the lack of opportunities presented to him by the larger society and found his niche in his native heritage.

Sources

Fuller, Todd. 60 Feet Six Inches, The (Baseball) Life of Mose YellowHorse. Duluth: Holy Cow Press, 2002.

Horowitz, Mikhail. "Wholly Mose." Elysian Fields Quarterly: The Baseball Review. 19:4 (Fall 2002), 77-80. (Review of Todd Fuller's 60Feet Six Inches and Other Distances from Home: The (Baseball) Life of Mose YellowHorse)

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: The Free Press, 2001.

The Pawnee Chief. April 16, 1964.

The Sporting News. March 19, 1921.

The Stillwater News Press. April 17, 1964.

People love stereotypes. One can force a group into a category without thinking about the individuals who make it up. After all, thought takes energy, and creators of stereotypes just might find out truths about people that they were blind to. What is worse, they might have to change their minds. The downside to such a high-minded dismissal of stereotypes, of course, is that they often contain an element of truth. Unfortunately, Mose J. YellowHorse for much of his life contributed to the stereotype of the drunken Native American.

Nevertheless, YellowHorse redeemed his dignity by living a life of atonement to himself and to his people. Since he played just two years in the major leagues, his redemption was not so much one of athleticism as of the soul. He stopped his drinking cold turkey and got a steady job. His people, once alienated from him, accepted him back and he became an elder in the Pawnee tribe. The tribe was always proud of him for his athletic achievements, but now they respected him for his beating drink and gaining steady employment. As an elder of the tribe, YellowHorse lent the wisdom and knowledge he gained from his trials to those who sought him out.

The Trail of Tears has never really ended. Native Americans were rounded up onto reservations much like concentration camps and denied their inalienable rights to the land they once roamed. Some shrugged it off as Manifest Destiny; others condemned it as outright robbery. Either way, eons of freedom came to an end for the Indians. They became strangers in their own land.

The Pawnees, rich in religion and mysticism and whose history went back many centuries, were herded into camps in the Oklahoma Territory. The tribe was divided into four bands: Skidi (Wolf Band), Kilkihaki (Little Earth Lodge Band), Tsawi (Asking for Meat Band), and Petahauirata (Man Going Downstream Band).

Clara and Thomas YellowHorse were children when the Pawnees were forced to relocate from Nebraska to Oklahoma in 1875. Though not as long a journey as the Trail of Tears, it was just as arduous, with many dying of disease and starvation. In 1879 the population of the Pawnees was reported at 1,440, a drop of fifty percent in 15 years. Thomas and Clara met in Oklahoma Territory, married (just when is not known), and settled down on a farm.

It was in Pawnee, Oklahoma Territory, that Mose J. YellowHorse was born on January 28, 1898. (Todd Fuller shows that the unusual spellings are correct in Sixty Feet 6 Inches.) The family belonged to the Skidi or Wolf Band of Pawnees. YellowHorse is considered by many to have been the first full-blooded American Indian to have played in the major leagues. Other Native Americans who played major league baseball such as Charles Albert (Chief) Bender, John (Chief) Meyers, and Lou Sockalexis were not believed to have been full-blooded natives.

Mose developed his pitching arm by throwing stones at small game to help feed the family. Powerfully built at 5'10" and 180 pounds but an amiable person, he was quick to make friends and had a great sense of humor.

Still, when he reported to Pittsburgh in 1921, he was both exhilarated and anxious as to how to conduct himself in a big industrial city with large steel plants and towering smokestacks, not to mention masses of humanity. Needing someone to help him adapt to the big city, he gravitated toward shortstop Rabbit Maranville, a notorious hellraiser, to say the least. The two became friends, rooming together on the road. They caroused and drank so much that Bill McKechnie, manager of the Pirates at that time, also roomed with them to keep an eye on the two crazies. One night McKechnie went out to catch a movie. Maranville and YellowHorse after some libation decided to catch pigeons as they sailed past their sixteenth-story window in the hotel. After nabbing their lot, they stuffed some of them into McKechnie's closet and the rest in YellowHorse's closet. When McKechnie returned from his movie, he found YellowHorse and Maranville sound asleep and thought himself a lucky man. Then he opened his closet and let out a howl as a flock of pigeons swarmed at him. Maranville awoke at this point and told McKechnie not to open YellowHorse's closet because his pigeons were in there. McKechnie understandably decided not to room with them anymore.

Because of his easygoing manner and sense of humor, YellowHorse got along somewhat more easily in the white man's world than most other Native Americans. The roles were reversed, however, when he took the mound. He was no longer the oppressed Indian; he was the guy with the hard round sphere that would be hurled at a white batter. On September 26, 1922, for example, YellowHorse was facing Ty Cobb in an exhibition game. Cobb as usual was crowding the plate and according to witnesses was hurling racist remarks at YellowHorse, who shook off four pitches and then sent a fastball that hit Cobb between the eyes. The Tiger bench rushed the mound, but YellowHorses's teammates ran out to protect him. Was the pitch intentionally sent at Cobb's head, or did it just get away?

The Pawnees appeared to have been assimilated more easily into the mainstream of Euro-American life than did other tribes. YellowHorse and his parents wore white men's clothes and lived in a permanent structure on their own farm. He attended school as ordered by the Indian Agency, an order intended to acculturate him into American society. With this background he fit more easily into the broader society. Despite this acculturation, there must have existed a pull to retain at least some ancient customs. For a millenium the Pawnees had a rich history, and they did not give it up easily. Indeed, YellowHorse was quite knowledgeable about his tribe's culture and augmented his knowledge all of his life.

YellowHorse started playing baseball at the Chilocco Indian School in Oklahoma. He went 17-0 in 1917 for the school. He then started his professional pitching career for the Arkansas Travelers of the Southern Association. Helping the team to its first championship in 1920, he went 21-7. Kid Elberfeld, his manager at Arkansas, had batted against Walter Johnson and felt that Mose was as fast as Johnson.

In 1921 YellowHorse came into the major leagues with the Pittsburgh Pirates, making his debut on April 15 in relief of Earl Hamilton in a 3-1 win over Eppa Rixey and the Cincinnati Reds. He made a few starts but was used mainly as a relief pitcher. Spending only two years with Pittsburgh, he had an 8-4 record and then hurt his arm in 1922.

YellowHorse's tenure with the Pirates was a time of great expectations for that did not pan out. Injuries and a drinking and carousing problem also inhibited his effectiveness. Still, he was a favorite with the fans, who would often chant, "Put in YellowHorse!" when the starting pitcher began to falter. Even after he was gone the chant could still be heard. In a game against the Cardinals on July 5, 1921, YellowHorse suffered a rupture in his arm that required surgery. This put him on the injured list for two months. Hurting his arm again in 1922 (possibly from a drunken fall) began his tailspin.

Aside from his drilling Cobb between the eyes in an exhibition game, there is nothing notable about his big league career other than that he lived the high life, eventually ruining his baseball career and making his life a living hell.

YellowHorse continued to live high-and drink. He loved being the roommate of Rabbitt Maranville, who had introduced him to the liquor that would become his personal demon. Maranville would eventually end his personal struggle with alcohol, but too late to help YellowHorse.

Sent to Sacramento in 1923, YellowHorse approached several major league clubs, but found no takers. His carousing and drinking problems were noted, and the big league teams passed on him. Back in Pawnee, his tribal members were unhappy about his drinking and he became alienated from them. His drinking was destroying his baseball career and his personal life. He had effectively ended his major league career by sustaining an injury to his arm, possibly as a result of his drinking. Now he was faced with not only losing his baseball career but also his personal dignity.

In 1924 YellowHorse suffered another serious arm injury. Sacramento traded him to Fort Worth; Fort Worth sent him back to Sacramento. In January of 1926, Sacramento sold Mose to Omaha, where he pitched in his final game on May 1. That was it for his baseball career.

YellowHorse's life was in free-fall when he returned to Pawnee. Drinking heavily and drifting from odd job to odd job, he was a lost soul. From 1927 to 1945 YellowHorse earned just enough to eat and drink. He was lost in his own tribe. His tribal brothers avoided him and talked about him in whispers. Suddenly in 1945 he quit drinking, apparently without any help. Mose YellowHorse's redemption took the form of retrieval. He retrieved his dignity by stopping drinking and finding himself gainfully employed in steady work. He retrieved his status with his tribe and became an honored member.

His life changed dramatically when he stopped drinking. He was now able to keep a steady job and in time became a tribal elder. He found steady work, first with the Ponca City farm team and then with the Oklahoma State Highway Department.

Chester Gould, also born on the Pawnee reservation, used YellowHorse in his Dick Tracy comic strip as the model for a character named YellowPony. YellowPony's face bore no resemblance to YellowHorse's. Nor did his speech, which was "ugh-me-know-you"-guttural English. YellowHorse actually spoke excellent English from his days in the agency school. The only real similarity between live model and comic strip character was a big, strong physique. Most likely, Gould knowingly perpetuated the stereotypical characteristics of the Indian in presenting YellowPony to help sell his comic strip. Sadly, the general public perceived the Indian as an uneducated if noble savage. In addition, the press also represented Indian ballplayers with an overwhelming physicality.

From 1945 until his death, YellowHorse lived a clean and respectable life. He became a groundskeeper for the Ponca City ballclub in 1947 and coached an all-Indian baseball team of youngsters who were all full-blooded. He hunted and fished and made decisions as an elder of the tribe.

Mose YellowHorse died on April 10, 1964. He was 66 years old. His headstone in the Northern Indian Cemetery in Pawnee curiously shows only the years of his birth and death but no dates. His gravesite is tucked away in a far corner of the Indian part of the cemetery separated from the white section by a long row of cedar trees. YellowHorse never married and had no children. The residents of Pawnee saw to it that he had a proper burial and headstone.

Though YellowHorse was not a household name, his life in and out of baseball raises many questions and opens many wounds about the relationship between Euro-Americans and Native Americans, now strangers in their own land and forced to assimilate themselves without benefits. For example, when Euro-Americans were celebrating the prosperity of the 1920s, Native Americans still on the reservations did not participate in the fruits of that prosperity. In effect they were not permitted to participate by the very absence of laws concerning them. Unlike the black people of that time who were restricted by many Jim Crow laws and knew where they stood, the Indians had no idea where they stood in the broader society. That they went to agency schools and learned Euro-American history and English meant nothing if they could not use their knowledge to participate in society as a whole. When some people pointed out that the Native American was a vanishing race, it was not solely because they did not exist; it was also their unfortunate lot to be ignored.

YellowHorse redeemed himself after a long bout with alcoholism and became a proud member of the Pawnee tribe. His life could have gone on with continuing alcoholism until it killed him. But instead he alone took his life into his own hands and redeemed himself. Deciding he was going in a direction that would only lead to self-destruction, YellowHorse made an abrupt but healthy u-turn. He rose above the lack of opportunities presented to him by the larger society and found his niche in his native heritage.

Sources

Fuller, Todd. 60 Feet Six Inches, The (Baseball) Life of Mose YellowHorse. Duluth: Holy Cow Press, 2002.

Horowitz, Mikhail. "Wholly Mose." Elysian Fields Quarterly: The Baseball Review. 19:4 (Fall 2002), 77-80. (Review of Todd Fuller's 60Feet Six Inches and Other Distances from Home: The (Baseball) Life of Mose YellowHorse)

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: The Free Press, 2001.

The Pawnee Chief. April 16, 1964.

The Sporting News. March 19, 1921.

The Stillwater News Press. April 17, 1964.