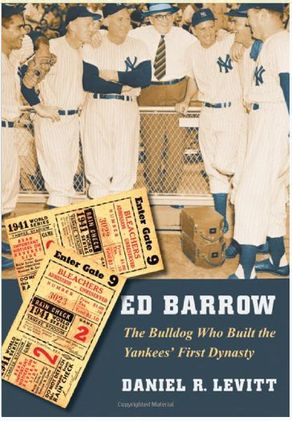

Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees' First Dynasty Paperback – March 1, 2010

With the death of Mercer, Angus needed to quickly find a new manager for 1903. On the recommendation of Ban Johnson, Angus approached Bar- row. Despite a pennant-winning team in Toronto, Barrow eagerly accepted a chance to manage for an apparently stable ownership in the Major Leagues. lust shy of thirty-five years old, Barrow had recently shaved his handlebar mustache; his more mature appearance befitted his new job. Recognizing his own Ii m it ations as an evaluator of baseball players, Angus also delegated the team-building function to his new manager. So, as in Toronto, Barrow had practically free rein to assemble the ball club as he saw fit (subject, of course, to Angus's oversight of the financial impact). 'lb restock the Tigers, Barrow targeted Eastern Leaguers (as opposed to National Leaguers), now that the fragile peace agreement was in effect. He contemplated bringing in Lou Bruce, his favorite utility player in Toronto, and pursued Jimmy Gard- ner, his star hurler of 1902. The Maple Leafs, though, held on to Gardner by offering him Barrow's manager position for 1903, and Bruce never appeared for the Tigers. To shore up his infield, Barrow signed Charles Carr, his first baseman in Toronto in 1901. He also swapped second basemen with the New York Giants, trading Kid Gleason (one of Elberfeld's pals) for Heinie Smith, whom Barrow had managed in Paterson and now named team cap- tain. To address the weakness at third base, Barrow converted pitcher (and occasional fielder) Joe Yeager to be his regular third baseman. Once again Barrow's aggressive tactics in pursing players generated some animosity. Carr was on the Jersey City reserve list, and the club publicly and vigorously objected to his signing with Detroit. Although the Na- tional Agreement was not yet technically reinstated, with the new peace agreement accepted in principle, a gentlemen's agreement to recognize re- serve rights of teams in Organized Baseball was generally in effect. Eastern League president Pat Powers, Barrow's old nemesis, protested the Carr sign- ing and threatened to invade American League cities if not fairly compen- sated. Johnson paid lip service to Powers's complaint, but Carr remained in Detroit. A couple of weeks later, Barrow further thumbed his nose at the Jersey City ownership (and Powers) by signing outfielder Wallace Clement. Barrow lost this round, however; later that spring he sent Clement back to Jersey City and signed Boston Brave discard Billy Lush. Unfortunately for his construction of the team, Barrow lost much of the month of February to pneumonia. Despite this setback, he remained op- timistic he could build a solid Major League ball club. For spring train- ing Barrow brought his squad to Shreveport, Louisiana, for two weeks of training and three weeks of exhibition games throughout the South. He also hoped to instill toughness and stamina by hiring middleweight fighter Willie Campbell to be his trainer for the spring. Back in Detroit the ream increased the seating capacity of Bennett Park by adding new bleachers to left field. Detroit opened at home against Cleveland on April n. Because Cleve- land's best pitchers were tall, Barrow ordered the mound lowered in the hope that this would increase their wildness. While this strategy may or may not have been the cause, Detroit swept all three games from the Indians. After this nice start, the team played around .500 ball and appeared materially improved over the dismal 1902 version. From the end of May through early June, Detroit played seven consecu- tive games against the St. Louis Browns. After winning the first, the Tigers lost the last six. Kid Elberfeld had been sulking for some time leading up to this series, and as reported in the Sporting News, lt so happened that in three of the six games lost to St. Louis, Elberfeld made a muff, fumble, or wild throw at the moment °fa critical stage, the error in each instance tak- ing the game away from Detroit." Elberfeld desperately wanted out of Detroit, which made Barrow suspicious of his errors. Other managers, includ- ing John McGraw of the Giants and Jimmy McAleer of the Browns, were clearly tampering with Elberfeld and encouraging him to force his release from the Tigers. While in St. Louis, McAleer and Elberfeld went so far as to have Elberfeld actually practice with the Browns while the Browns reg- ular shortstop, future Hall of Famer Bobby Wallace, shifted to third. When Elberfeld fielded particularly egregiously on June t after a return to Detroit—a game the Tigers lost after Elberfeld booted a routine double play with one out and the team up by two in the ninth—Barrow could stand it no longer. He confronted Elberfeld after the game and blistered him with his disgust. Despite his small stature, the hard and violent Elberfeld refused to be cowed by Barrow's indignation. Elberfeld offered to buy his release from the Tigers for one thousand dollars, claiming he had been offered a salary in excess of three thousand dollars. Elberfeld clearly hoped to force his way to either the St. Louis Browns or back to the Giants. Bar- row angrily declared that after his actions he would never trade Elberfeld to one of those two teams. Barrow, with Angus's acquiescence, fined Elberfeld two hundred dollars, suspended him indefinitely, and released a damning statement to the press: "He utterly disregarded the rules and regulations, refused to obey the or- ders of his captain and manager to such an extent that we feel called upon to put a stop to it. I thought he tried to lose some of the games while we were in the South [i.e., at St. Louis], but said nothing about it." Barrow's public accusation of deliberately throwing the game ended any possibility of a reconciliation in Detroit (assuming that either side wanted one in the first place). As an above-average shortstop, Elberfeld was a valuable player, although his reputation likely exceeded his ability. When it became clear that Elberfeld was available, a number of teams approached Barrow and An- gus for their asking price. Elberfeld, however, continued to insist he would only go to the Browns or the Giants; otherwise he would jump to an out- law league on the Pacific Coast or retire home to Tennessee. To relieve the stalemate Ban Johnson and White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, another key league executive, traveled to 'Detroit CO meet with Barrow and Angus. Comiskey had some limited hopes of landing Elberfeld for himself. Johnson, however, had broader objectives: he feared the nega- tive publicity of a prolonged stalemate with one of the league's star players, including a potential jump back to the National League. Furthermore, he recognized an opportunity to strengthen the New York American League club (today known as the Yankees). Disregarding the suspension, Johnson was determined to reach a resolution compatible with his objectives. To this end, although Barrow argued for a greater return, Johnson helped en- gineer a trade with New York manager Clark Griffith for shortstop Her- man Long, a one-time great shortstop now well past his prime, and Ernie Courtney, a journeyman third baseman. Cincinnati purportedly offered four thousand dollars for Elberfeld; it is unlikely the cash-strapped Angus would have turned this down but for Johnson's influence. Given the charged atmosphere of the time, one should not be surprised that Johnson's machinations did not end the controversy. Elberfeld agreed to join the Yankees, but NewYork Giants owner John Brush, a reluctant supporter at best of peace with the American League, loudly protested the move. He had lost Elberfeld in the peace settlement and was now witness- ing him come to New York to star for his direct competitor. In retaliation Brush attempted to legally enjoin Elberfeld from appearing with the Yan- kees. He also convinced National League president Harry Pulliam that the trade violated the peace agreement. Brush should, therefore, be permitted to play his own disputed shortstop, George Davis. The peace agreement had awarded Davis to the Chicago White Sox, but Davis had held out rather than report. Brush's playing of Davis clearly violated the settlement and threatened to reignite the baseball war bet ween the leagues. Only pressure from the other National League owners, most importantly Cincinnati's Garry Herrmann, induced Brush to back down. He reluctantly agreed to withdraw his injunction request and stop playing Davis. Barrow received considerable criticism in the press for his inability to control Elberfeld and the resulting far-reaching complications. The, e can be little doubt that Barrow's dictatorial and overbearing style chafed the in- dependent-minded Elberfeld, but Elberfeld was predisposed to resent any manager after his forced return to Detroit. Elberfeld's outlook further deteriorated when Barrow named Heinie Smith, the player his friend Kid Gleason had been traded for, team captain instead of him. Barrow remained enamored with the fight game. While in Boston shortly after his confrontation with Elberfeld, he attended a boxing match along with several Detroit and Boston players. Seated close by was Sandy Ferguson, a local Boston heavyweight of some renown. Ferguson quickly be- came drunk and obnoxious with the patrons seated near him. Eventually he challenged Barrow. Wound up after watching a boxing match and in a general state of anger over the Elberfeld incident, Barrow readily accepted. He landed the first punch to Ferguson's stomach, stunning the big fighter. Fortunately, before Ferguson could retaliate, Boston first baseman Candy LaChance jumped in and separated the two men. At the end of July the Tigers stood 41-40, and Barrow hoped to fine-tune his club, both for the pennant race and the upcoming 1904 season. He maintained his aggressive posture on signing ballplayers regardless of their status. When he learned that Jimmy Gardner was in clanger of losing his Toronto managerial position to Arthur Irwin, Barrow contacted his ex-hurler with an offer of $2,500. Gardner declined the offer, most likely because he was under contract with the Maple Leafs and not free to jump. Barrow also conceded that the trade for Smith was a mistake; in August he released his captain, who assumed the manager's job at Rochester in the Eastern League. To rebuild his depleted middle infield, Barrow once again tried to sidestep Minor League rights and signed John Burns, most recently in an outlaw league in California. The National Commission, however, ruled that Burns was still technically the property of Toledo, and Detroit had to return him. Eventually, because Burns coincidently happened to be on Detroit's draft list, Ban ow worked our an agreement whereby Detroit could acquire him by paying Toledo $750. Barrow remained unrepentant about skirting the lines of Minor League player rights. When he read that the National Association had failed once again to ratify the latest draft of the National Agreement, Barrow "chuckled" and remarked: If they will only stick to that a few days until I can close a few deals with Eastern League players, I'll have my 1904 team complete. Barrow dickered with his old friend George Stallings, now manager at Buffalo, to acquire a couple of players for the 1904 season. Stallings agreed to sell outfielder Matty McIntyre and pitcher Al Ferry if Barrow would also include a couple of players in return. When Ernie Courtney (a player Barrow never really wanted in the first place) refused to be one of them, Barrow suspended him, claiming he was out of shape and playing poorly. Barrow and Stallings then agreed on several players to be named later in the fall. For such a trade, Barrow needed the consent of the other seven American League owners (so that they would not put in a waiver claim on the players being shipped to the Minors). Because the other owners also often traded or sold players to the Minot League teams, a gentlemen's agreement of a "round robin truce' was generally in effect, to the detriment of the players.

Product Details

Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees' First Dynasty Paperback by Daniel R. Levitt (Author) Before the feuding owners turned to Ed Barrow to be general manager in 1920, the Yankees had never won a pennant. They won their first in 1921 and during Barrow’s tenure went on to win thirteen more as well as ten World Series. This biography of the incomparable Barrow is also the story of how he built the most successful sports franchise in American history. Barrow spent fifty years in baseball. He was in the middle of virtually every major conflict and held practically every job except player. Daniel R. Levitt describes Barrow’s pre-Yankees years, when he managed Babe Ruth and the Boston Red Sox to their last World Series Championship before the “curse.” He then details how Barrow assembled a winning Yankees team both by purchasing players outright and by developing talent through a farm system. The story of the making of the great Yankees dynasty reveals Barrow’s genius for organizing, for recognizing baseball talent, and for exploiting the existing economic environment. Because Barrow was a player in so many of baseball’s key events, his biography gives a clear and eye-opening picture of how America’s sport was played in the twentieth century, on the field and off. A complex portrait of a larger-than-life character in the annals of baseball, this book is also an inside history of how the sport’s competitive environment evolved and how the Yankees came to dominate it.

Product Details

Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees' First Dynasty Paperback by Daniel R. Levitt (Author) Before the feuding owners turned to Ed Barrow to be general manager in 1920, the Yankees had never won a pennant. They won their first in 1921 and during Barrow’s tenure went on to win thirteen more as well as ten World Series. This biography of the incomparable Barrow is also the story of how he built the most successful sports franchise in American history. Barrow spent fifty years in baseball. He was in the middle of virtually every major conflict and held practically every job except player. Daniel R. Levitt describes Barrow’s pre-Yankees years, when he managed Babe Ruth and the Boston Red Sox to their last World Series Championship before the “curse.” He then details how Barrow assembled a winning Yankees team both by purchasing players outright and by developing talent through a farm system. The story of the making of the great Yankees dynasty reveals Barrow’s genius for organizing, for recognizing baseball talent, and for exploiting the existing economic environment. Because Barrow was a player in so many of baseball’s key events, his biography gives a clear and eye-opening picture of how America’s sport was played in the twentieth century, on the field and off. A complex portrait of a larger-than-life character in the annals of baseball, this book is also an inside history of how the sport’s competitive environment evolved and how the Yankees came to dominate it.

- Paperback: 456 pages

- Publisher: Bison Books (March 1, 2010)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 080322981X

- ISBN-13: 978-0803229815

- Product Dimensions: 8.9 x 6 x 1 inches

- Shipping Weight: 1.2 pounds

- Average Customer Review: 4.8 out of 5 stars

- Amazon Best Sellers Rank: #2,089,573 in Books