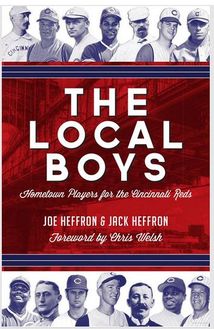

The Local Boys: Hometown Players for the Cincinnati Reds By Joe Heffron, Jack Heffron

The Local Boys

NORMAN "KID" ELBERFELD

APRIL 13, 1875 - JANUARY 13, 1944

Major League Career

1898-1914

Time as a Cincinnati Red

1899

Position

SHORTSTOP; THIRD BASE

DURING AUGUST OF 1899, 24-year-old Norman "Kid" Elberfeld, Detroit's star shortstop, was living at the family home in Norwood on what the Enquirer termed "enforced vacation" from the Western League—which would become the American League in 1901—for being ejected from too many games and for attacking an umpire. Known as a violent hothead, he earned his nickname--"The Tabasco Kid." Though just 5'7" and 150 pounds, he played with a ferocity that made opponents—and umpires—think twice before challenging him. Even legendary badass Ty Cobb kept his distance after Elberfeld rubbed his face in the dirt following a head-first slide into second base. "I was a sorry mess when I picked myself up," Cobb recalled years later in his book, Inside Baseball with Ty Cobb.

But without a team, or a paycheck, during that August, he hoped his hometown Reds would sign him, so he wooed the press. Sounding wooed, the Enquirer called him a "gentlemanly player who is just a trifle over-earnest in his endeavor to win."

Elberfeld was born in Pomeroy, Ohio, about 150 miles east of Cincinnati, moving with his family (he was the youngest of eight children) when he was 3 to Norwood. His older brother Wes taught him the game and coached him on an amateur team in Bond Hill. Primarily a shortstop but able to play second and third, he became known for his great range, rocket arm, and savage competitive spirit. He also hit well, batting over .300 four times in his 14-year Major League career, but his true skill was getting on base, compiling a lifetime .355 on-base percentage. In his later years, he talked about how he could shift his body to look like he was trying to avoid a pitch even as he as was leaning into it. He ranks 16° on the all-time Major League list of career hit-by-pitches.

In hopes of a contract with the Reds, he showed up at the Central Union Station (located at Third and Central), meeting manager Buck Ewing and the team when they returned from a road trip. While waiting, he told reporters that he blamed his suspension on the umpires, who he said were unfair. "Every time I was hit with a pitched ball they acted as though I had intentionally got in the way," he said.

The Enquirer described him as "a stockily built, well-dressed youngster" and "the last person any one would suspect of being a brawler or a troublemaker." He told them, "This is my home city, and nothing would please me better than to play with the Reds."

During that August, the Reds were on a roll—winning 14 straight games, still the franchise record. They had begun the season slowly due to injuries, but now were hitting stride and Elberfeld could help. Detroit didn't want to give him up permanently, but they sold him in a conditional deal.

He debuted with the Reds on August 26 and played nearly every game for the rest of the season, scoring 23 runs and posting a slash line of .261/.378/.319 in 166 plate appearances. He also behaved himself. When the season ended, he returned to Detroit—and to his old ways, getting another suspension the following year. In 1903, the Reds offered Detroit $4,000 for his contract, but he went to the Highlanders instead. He played in the majors until 1914, retiring at 39.

By then he had bought a farm near Chattanooga, Tennessee, but he also coached for many years in the minors. He also trained his five daughters to play basketball, forming a barnstorming team called The Elberfeld Sisters. He died of pneumonia in 1944, a legendary and polarizing figure.

"My impression was that on the field he was extremely tough, and often mean," says John Elberfeld, his grandnephew, who has researched Kid for 20 years and posts his findings online at kidelberfeld.com. "But he did raise five daughters and a son and a step-son and they seemed to have had a happy childhood. He was devoted to them. He was also devoted to developing young players." If the Reds had managed to hold him, they might have had more success and surely would have had, as the Enquirer observed during his short time with the team, "more life and ginger."

NORMAN "KID" ELBERFELD

APRIL 13, 1875 - JANUARY 13, 1944

Major League Career

1898-1914

Time as a Cincinnati Red

1899

Position

SHORTSTOP; THIRD BASE

DURING AUGUST OF 1899, 24-year-old Norman "Kid" Elberfeld, Detroit's star shortstop, was living at the family home in Norwood on what the Enquirer termed "enforced vacation" from the Western League—which would become the American League in 1901—for being ejected from too many games and for attacking an umpire. Known as a violent hothead, he earned his nickname--"The Tabasco Kid." Though just 5'7" and 150 pounds, he played with a ferocity that made opponents—and umpires—think twice before challenging him. Even legendary badass Ty Cobb kept his distance after Elberfeld rubbed his face in the dirt following a head-first slide into second base. "I was a sorry mess when I picked myself up," Cobb recalled years later in his book, Inside Baseball with Ty Cobb.

But without a team, or a paycheck, during that August, he hoped his hometown Reds would sign him, so he wooed the press. Sounding wooed, the Enquirer called him a "gentlemanly player who is just a trifle over-earnest in his endeavor to win."

Elberfeld was born in Pomeroy, Ohio, about 150 miles east of Cincinnati, moving with his family (he was the youngest of eight children) when he was 3 to Norwood. His older brother Wes taught him the game and coached him on an amateur team in Bond Hill. Primarily a shortstop but able to play second and third, he became known for his great range, rocket arm, and savage competitive spirit. He also hit well, batting over .300 four times in his 14-year Major League career, but his true skill was getting on base, compiling a lifetime .355 on-base percentage. In his later years, he talked about how he could shift his body to look like he was trying to avoid a pitch even as he as was leaning into it. He ranks 16° on the all-time Major League list of career hit-by-pitches.

In hopes of a contract with the Reds, he showed up at the Central Union Station (located at Third and Central), meeting manager Buck Ewing and the team when they returned from a road trip. While waiting, he told reporters that he blamed his suspension on the umpires, who he said were unfair. "Every time I was hit with a pitched ball they acted as though I had intentionally got in the way," he said.

The Enquirer described him as "a stockily built, well-dressed youngster" and "the last person any one would suspect of being a brawler or a troublemaker." He told them, "This is my home city, and nothing would please me better than to play with the Reds."

During that August, the Reds were on a roll—winning 14 straight games, still the franchise record. They had begun the season slowly due to injuries, but now were hitting stride and Elberfeld could help. Detroit didn't want to give him up permanently, but they sold him in a conditional deal.

He debuted with the Reds on August 26 and played nearly every game for the rest of the season, scoring 23 runs and posting a slash line of .261/.378/.319 in 166 plate appearances. He also behaved himself. When the season ended, he returned to Detroit—and to his old ways, getting another suspension the following year. In 1903, the Reds offered Detroit $4,000 for his contract, but he went to the Highlanders instead. He played in the majors until 1914, retiring at 39.

By then he had bought a farm near Chattanooga, Tennessee, but he also coached for many years in the minors. He also trained his five daughters to play basketball, forming a barnstorming team called The Elberfeld Sisters. He died of pneumonia in 1944, a legendary and polarizing figure.

"My impression was that on the field he was extremely tough, and often mean," says John Elberfeld, his grandnephew, who has researched Kid for 20 years and posts his findings online at kidelberfeld.com. "But he did raise five daughters and a son and a step-son and they seemed to have had a happy childhood. He was devoted to them. He was also devoted to developing young players." If the Reds had managed to hold him, they might have had more success and surely would have had, as the Enquirer observed during his short time with the team, "more life and ginger."